When the French visited Liverpool again - A large game of Pluie de Balles.

by Jorit Wintjes

I. Introduction

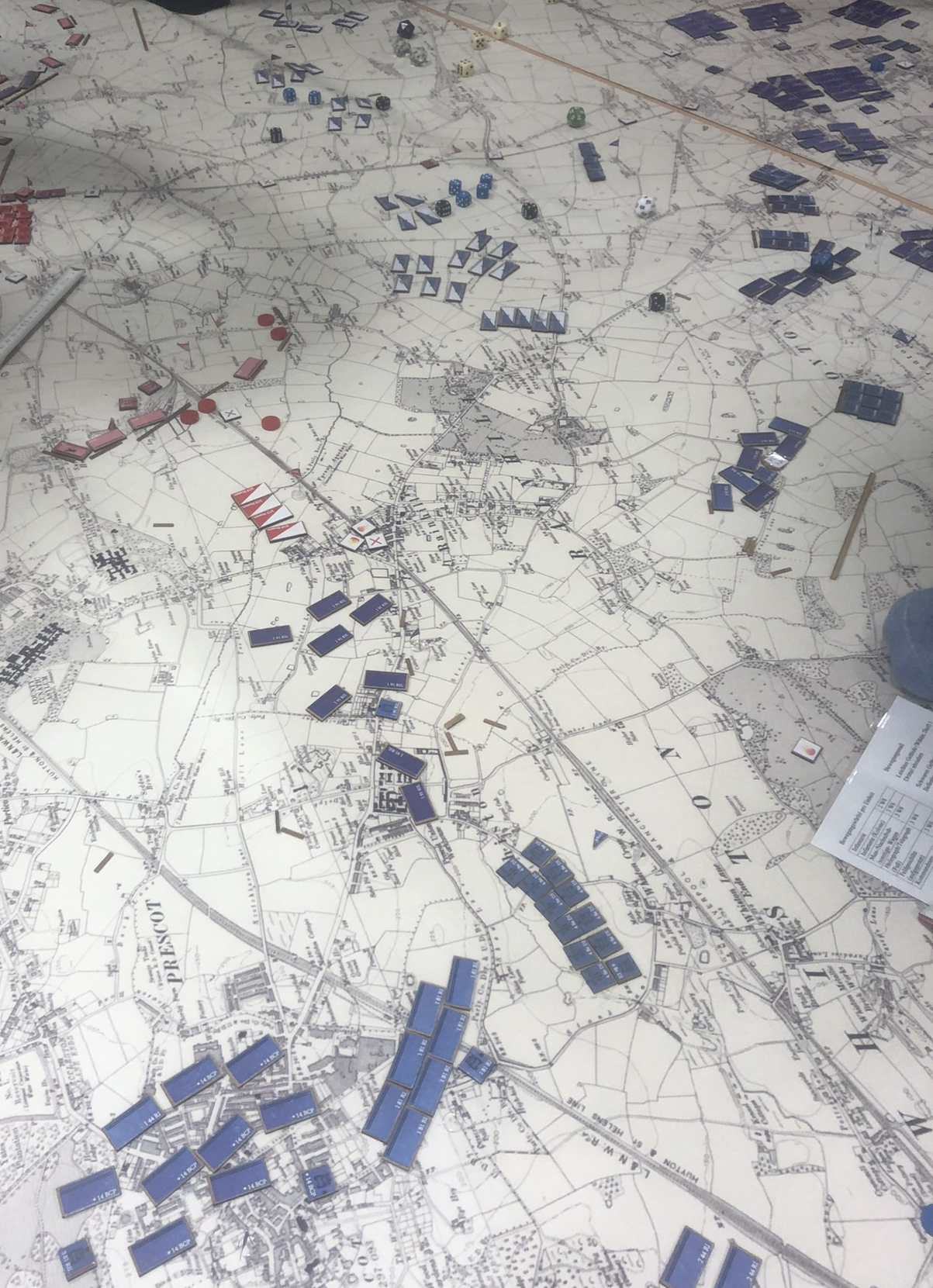

In February 2023 the Conflict Simulation Group ran another big game of Pluie de Balles at a German service university, using the same scenario covering a French landing in Liverpool as it had done in November last year; for a report of that game see elsewhere on this page.

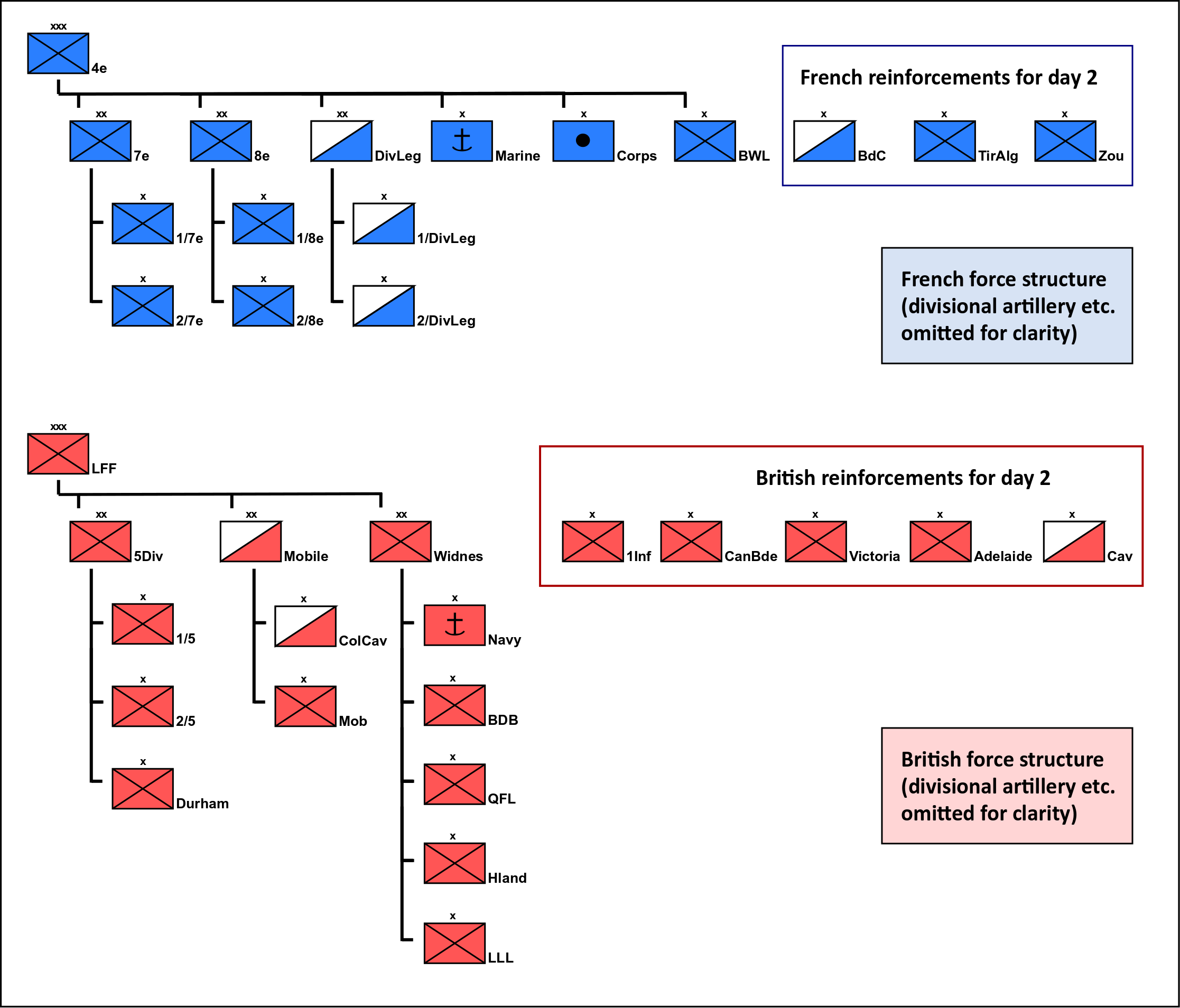

The overall setup was nearly identical, with only a few minor modifications - instead of having one division and several independent brigades, British forces were organised in three division-size units - an infantry division, a mobile division including a cavalry brigade and a brigade of mobile infantry, and a hotchpotch division formed around a naval brigade and a number of smaller volunteer brigades -, slightly reducing their operational mobility. French force structure was identical, with two infantry divisions, a cavalry division, a naval brigade and a brigade of heavy artillery available on the first day and two experienced infantry brigades and an elite cavalry brigade scheduled for reinforcements on the second day.

An overview over French and British force structures.

The arrival of the French reinforcements was again tied to the French not only controlling the harbour of Liverpool itself but also the Wirral peninsula’s coastline opposite the harbour. This had proved to be the French’s undoing in November, when, after losing control over the Wirral Peninsula on the first day, no reinforcements arrived on day two. Things would play out very differently the second time around.

II. Plans galore!

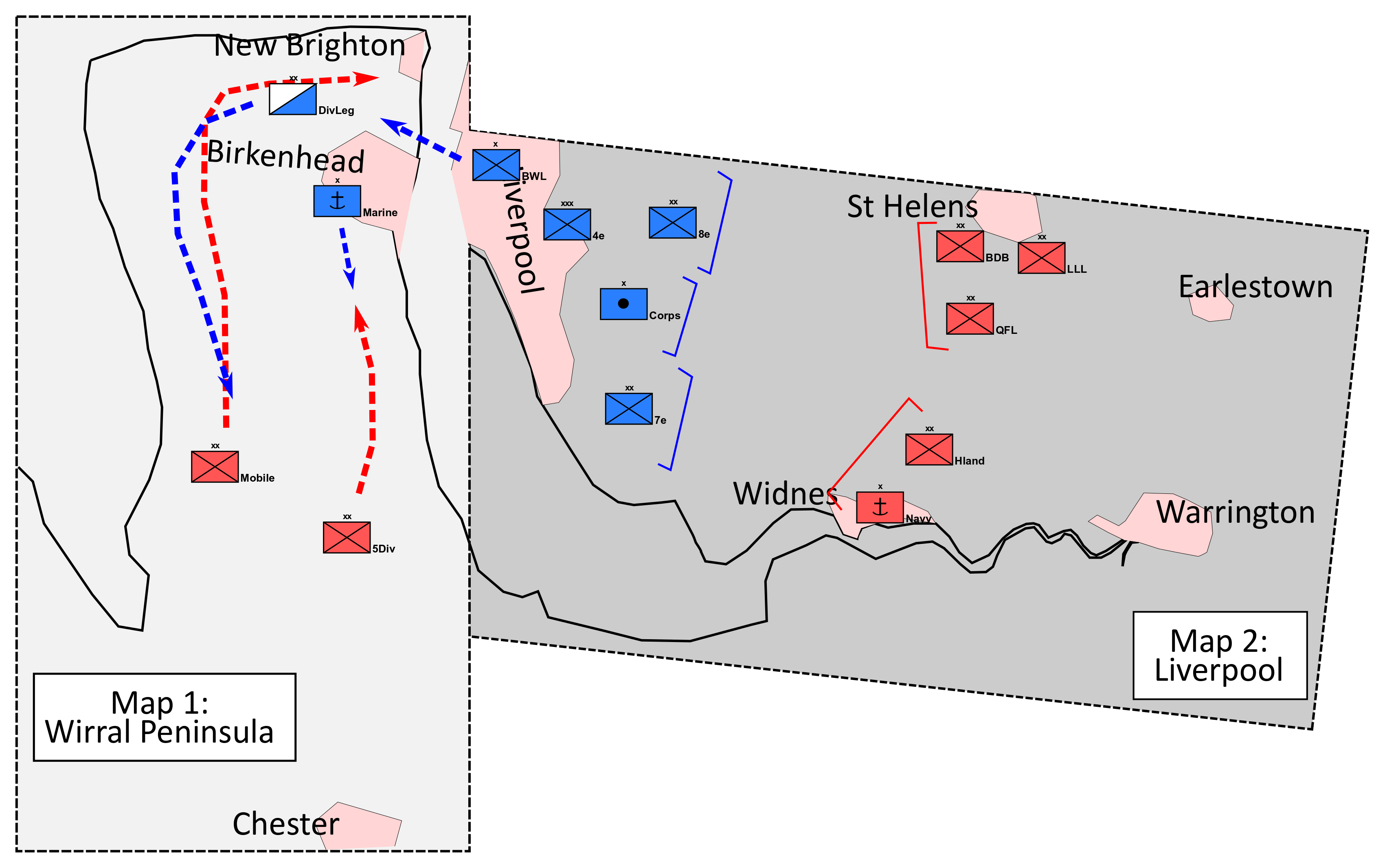

The British plan was simple: the infantry division and the mobile division were deployed on the Wirral Peninsula, the latter tasked with attacking Birkenhead and tying down any French defenders of the city, the former ordered to swing around the city and occupy the coastline around New Brighton as quickly as possible and cover the harbour with its batteries. Meanwhile, east of Liverpool the makeshift division built around the naval brigade had to hold Runcorn and Warrington as long as possible in the face of an expected French onslaught.

British and French starting positions and plans for day 1.

The plan was fundamentally sound, but the French had other things in mind. They deployed their two infantry divisions as well as their heavy artillery east of Liverpool, while, correctly assessing that the ground was fairly difficult there for exploiting its full potential, assigning their cavalry division to the Wirral Peninsula; it was to push southwards and attack towards Chester. Instead of facing just a brigade in Birkenhead which could be tied down by a frontal assault, leaving space to wheel around the city, British mobile forces now found themselves facing a determined and capable enemy who was also aware of the importance which the coastline around New Brighton had.

The British Mobile Division.

5 Division in its starting positions.

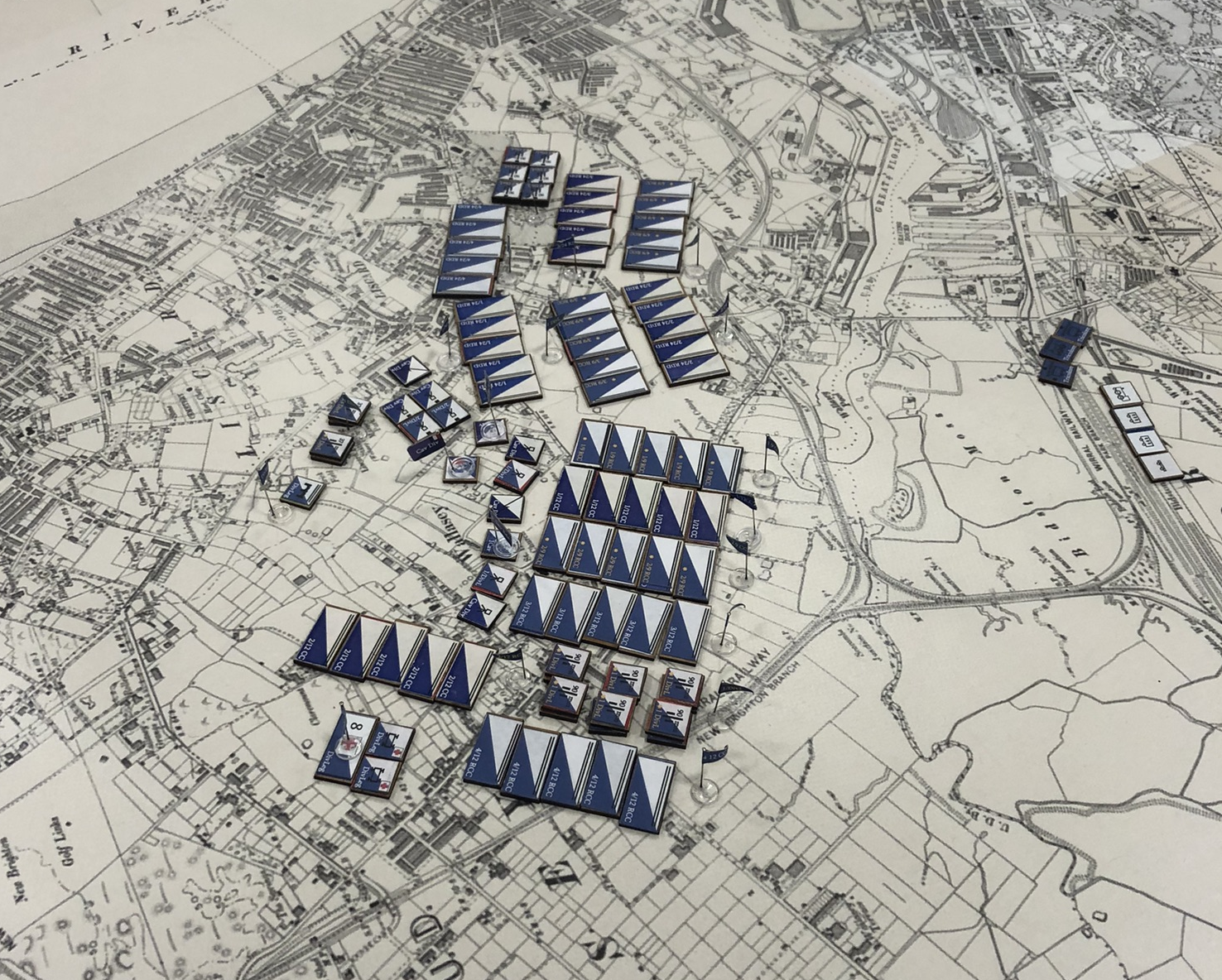

The French Cavalry Division.

French positions south of Birkenhead.

The French in turn, expecting the British blow to fall on Liverpool from the east, ordered their two infantry divisions to dig in on day one and, supported by all the heavy artillery, defend their positions - against an enemy who, at perhaps a third of the French strength, never had any intentions to go on the offensive.

The French Line east of Liverpool.

III. The course of the battle.

As a consequence, the first day saw comparatively little fighting east of Liverpool, apart from a few skirmishes caused by French commanders getting restless and British commanders overconfident. Notably a French unit of French sailors on bicycles managed to push well into the British rear and cut several telegraph lines, creating command and control difficulties for their opponents. However, wary of developments on the Wirral Peninsula and still expecting a British attack to be launched, the French staff decided against going on the offensive for most of the first day.

Meanwhile, things on the Wirral Peninsula had developed very differently. While the British infantry division was moving northwards to attack Birkenhead, the mobile division had surged forward, only to find their line of march blocked by the French cavalry division.

French cavalry division in action.

After several hours of bitter and hectic fighting, the British mobile division, had to break off its attack, having been reduced to about a third of its original strength. At the same time the infantry assault on Birkenhead had ground to a halt in the southern suburbs, and during the day French forces had been further reinforced by infantry units in brigade strength.

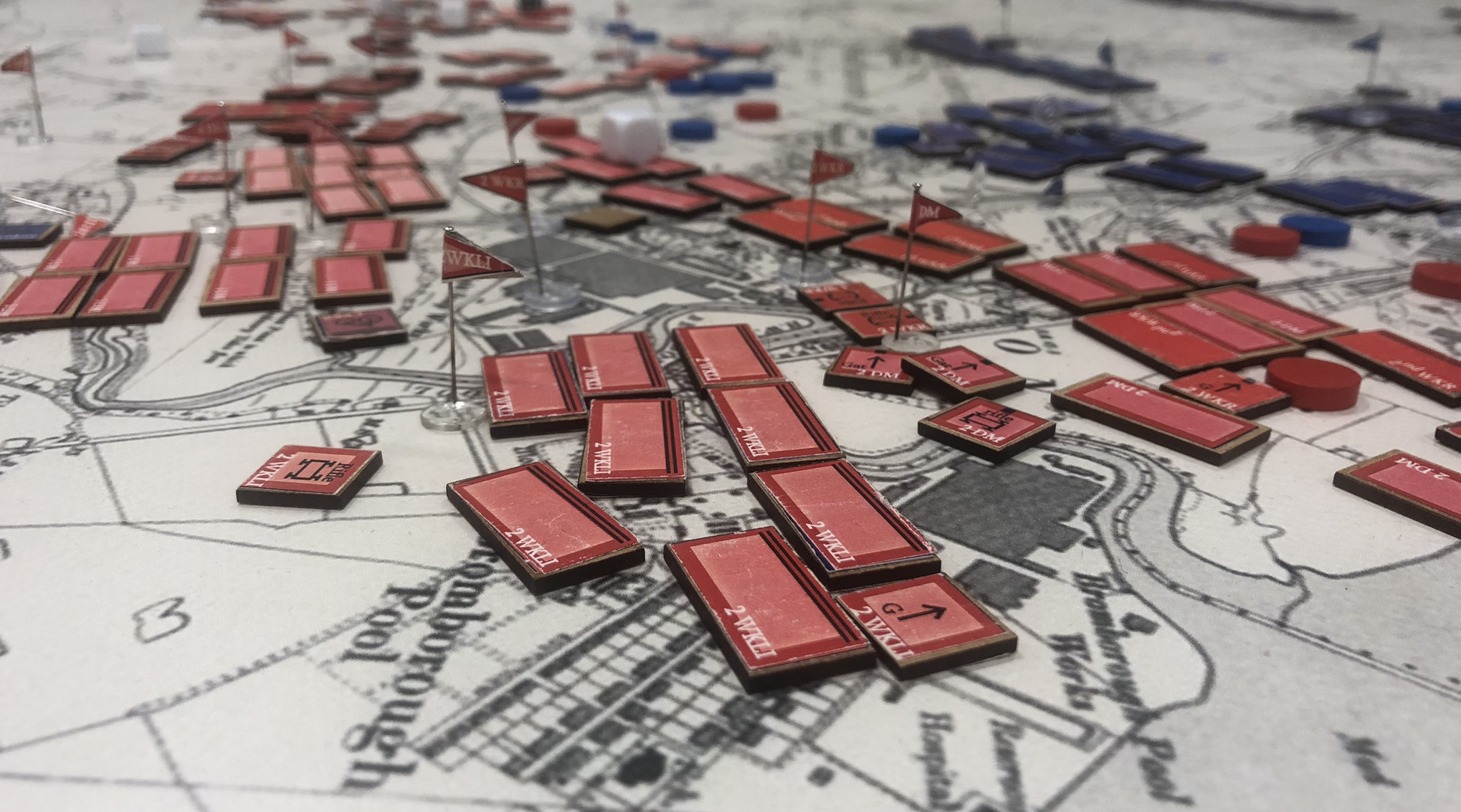

Fighting in the southern suburbs of Birkenhead.

At the end of day 1, things did not look too good for the British team. Their attack on Birkenhead had produced little meaningful gains against heavy losses, while French probes against the defences around Runcorn had shown that even after sending a brigade’s worth of infantry across the Mersey, a French assault was still likely to succeed given their heavy artillery support; as one would expect from an arms of service that produced Napoleon French artillery, again expertly handled, inflicted considerable losses on the enemy.

The remnants of the British Mobile Division.

The overall situation on the Wirral Peninsula at the end of day 1.

Correctly assessing the situation east of Liverpool to be difficult, and being relieved of guarding the bridge at Runcorn as a stray 270mm shell brought it down early in the afternoon, the British staff decided to pull back their forces to a defensive line around Warrington. French spirits certainly were up on that evening, while the mood in the British staff room was one of impending doom.

The overall situation east of Liverpool at the end of day 1.

The second day saw reinforcements arrive on both sides. While the French added two experienced infantry brigades and an elite cavalry brigade to their forces, the British gained an elite cavalry brigade, two infantry brigades and some additional artillery batteries and cavalry squadrons. Realizing the importance of gaining the coastline north of Birkenhead, both sides committed further forces to the Wirral peninsula; the French initially sent a brigade of Zouaves into Birkenhead, while the British added their elite cavalry brigade, one infantry brigade and several batteries of artillery to their depleted forces. East of Birkenhead the French elite cavalry was deployed, as was a brigade of experienced Tirailleurs Algeriennes, while the remaining British units joined the defensive lines around Warrington, expecting a French attack.

British reinforcements on the Wirral Peninsula.

French reinforcements on the Wirral Peninsula.

That attack did eventually materialize, though from the British perspective it appeared to be half-hearted at best; French forces pushed towards Runcorn and actually captured the village, only to later give it up again and fall back onto their old positions. The cavalry brigade was observed moving towards the front and back again, as did the tirailleurs Algeriennes. Something was clearly happening on the Wirral peninsula that had a seriously disruptive effect on French planning, and only in the very last hours of the second day did French forces, now significantly reduced in size, mount a last attack of sorts, with their cavalry brigade trying in vain to push through British defences.

Last French attack against Warrington.

Events on the Wirral peninsula had indeed been decisive. Undaunted by their lack of success on the prior day, the British again attacked vigorously, and this time it was the French who suffered badly. Within a few hours the French cavalry division, fighting a brave but increasingly desperate rearguard action against British cavalry forces, was all but destroyed, while the British infantry division, now supported by both heavy artillery and an additional infantry brigade, finally made significant progress.

The British Cavalry Brigade breaks through French lines.

British forces pushing towards New Brighton.

As British forces were entering Birkenhead and pushing in French lines, the French tried to feed reinforcements into Birkenhead, initially across their pontoon bridge and after its destruction through the railway tunnel until a stray 12in shell put an end to that as well, effectively cutting off French forces in Birkenhead. With the French perimeter becoming smaller, French commanders had to face the problem of having less and less space in which to deploy their forces, at the same time creating concentrations where it was nearly impossible even for the highly inacccurate British heavy artillery not to hit anything.

Birkenhead in the early afternoon.

At the end of the day, British forces on the Wirral Peninsula, while having suffered further not insignificant losses throughout the day, had managed to utterly destroy French forces in Birkenhead. As the French staff, well aware of the crucial importance of the coastline north of Birkenhead, had poured significant resources into that fight, the two divisions east of Liverpool were seriously reduced in capability, and their last attack was more of a face-saving measure than anything else.

Depleted French forces east of Liverpool.

Situation in Birkenhead at the end of day 2.

Fearing a British push across the Mersey into their rear the French finally decided to set fire to the city centre in Liverpool, which caused an armed mob of angry citizens to form outside French corps HQ, which was unprotected in the French rear; after that mob had thoroughly ransacked the French HQ and captured the French staff, the umpires decided to call it a day.

Situation east of Liverpool at the end of day 2.

IV. Some final thoughts.

British victory was complete. Not only did French forces find themselves basically in the middle of nowhere, with no harbour to supply them for the following days and even the city of Liverpool unavailable as a base, they had also suffered extremely heavy losses, amounting to two thirds or more of their initial strength. British forces, on the other hand, were not only substantially intact east of Liverpool and had by the end of the day even gained numerical equality if not superiority in some places, they had also captured the crucial coastline of New Brighton and even managed to push back into Runcorn as French forces had given up their gains later in the afternoon. British losses had been heavy during fighting on the Wirral peninsula, but were negligible east of Liverpool. The Liverpool Field Force had carried the day, handily.

A few final thoughts. First of all, again all sides showed great determination and willingness to endure the hardships of a two-day wargame during which the staff teams were essentially locked up in their staff rooms while the force commanders spent literally hours on their knees on the huge maps, living essentially in two-minute-terms. Then, while the scenario was quite similar to that of last November, it turned out very differently, and unexpectedly so. At the end of day 1 things looked promising for the French, only to turn around during the morning of the second day. The French decision not to launch an all-out attack on the first day east of Liverpool was understandable given their worry about a British attack, but as that attack did not materialize during the day, and with British forces being seriously outnumbered east of Liverpool, ditching the plan at some point during the first day might have given the French sufficient momentum to put more pressure on the British, which in turn could have caused them to divert more reinforcements to that area. And finally, observing the staff teams was quite interesting as well.

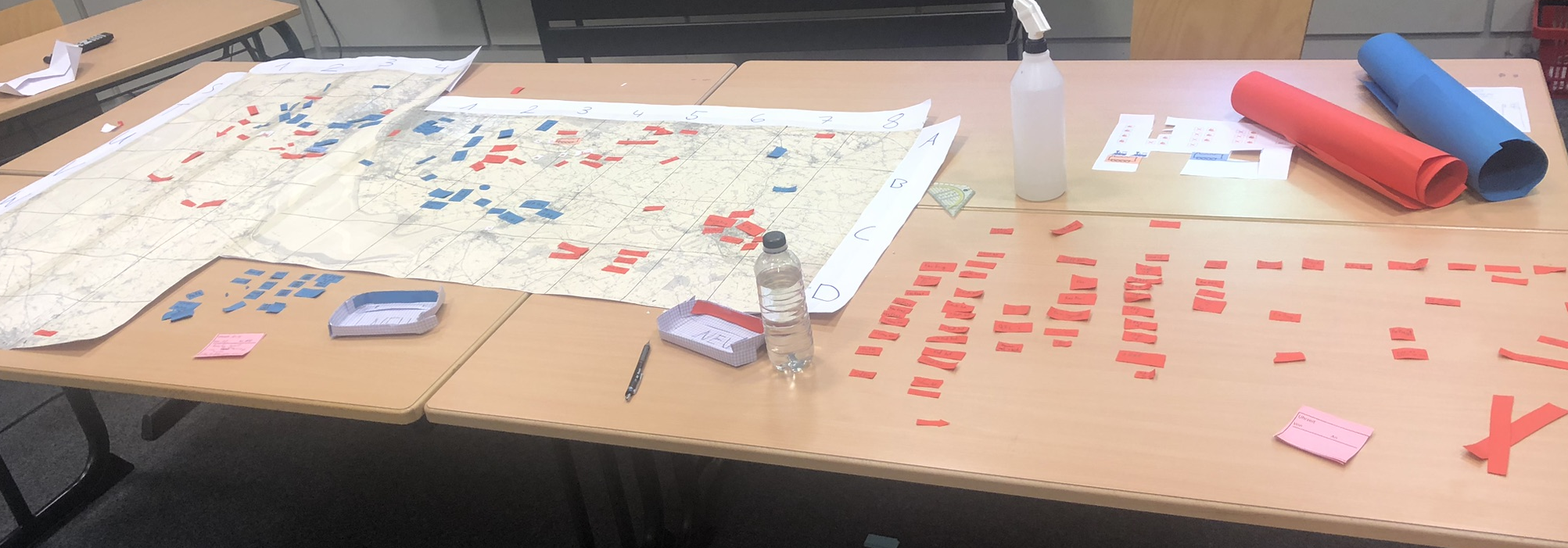

The map in the French staff room.

The French staff team worked almost like an oiled machine, and to the credit of the French staff they continued their work with determination even in the face of setbacks that grew ever more serious as time progressed. The British staff for much of the first day was essentially comprised of just one person, with a second mainly acting as messenger; this turned out to be a textbook case of why it is useful to have a staff, as having to do all the information processing as well as decision making alone without anyone to consult with was not only obvously stressful but also at times producing rather questionable decisions; it is all the more applaudable that in the face of these difficulties the British staff managed to put together a good plan for the second day. All in all the wargame once again showed that Pluie de Balles excels at involving large numbers of participants, and can be really stressful for everybody involved - except perhaps for the umpires.