Kriegsspiel in the 21st c.? And with 19th c. scenarios at that?

by Jorit Wintjes

Introduction.

This brief blog entry covers the question we are probably asked most often - well, on reflection it likely comes a distant second to “What on earth is happening out there?”, which is usually uttered with both increasing frequency and mounting dispair during Kriegsspiele by the participants - when running Kriegsspiele with military decision makers: is there any practical relevance to running 19th c. scenarios in the second decade of the 21st c.? At first, this appears to be a very relevant question. After all, the battlefields of the mid- to late 19th c., where most of CoSimG’s Kriegsspiele currently take place, where characterised by two-dimensional warfare and thus a far cry from the modern battlespace which extends into dimensions the eye cannot see. So it seems logical to question the usefulness of, for example, cavalry-related knowledge in a world where hills still shake with thunder riven when cavalrymen charge into battle, but where the latter rush their armoured vehicles instead of furiously neighing steeds.

However, it is important not to lose sight of what the Kriegsspiel is actually about: while it was originally used mainly as a tactical simulation, in its developed form it was precisely not about wrestling with the minutiae of tactics but rather about experiencing the greatest problem of military decisionmaking at all - to find out when it is necessary to break with one’s initial plan - in a situation of increasing friction caused by the unfolding battle. The fully developed Kriegsspiel was not primarily used to learn or exercise the application of tactics; rather, its aim was to push participants to the limits of their comfort zone, and beyond, where they still had to make decisions - or face defeat.

What Kriegsspiel is really about.

That the Kriegsspiel was fundamentally about the experience of decision-making under stress caused by friction, and not merely about tactical minutiae finds ample support in the surviving evidence. Already the general setup of all Kriegsspiel rules points into that direction: while the Prussians introduced a “red” force (which was cunningly identified as friendly when the British Army introduced the Kriegsspiel in 1872, because, well, it was red - but that is a story for another blog entry), they never bothered to come up with “red” army lists. Of course, in the 1820s that was still quite irrelevant, as weapon systems and their capabilities throughout Europe differed only in comparatively small details; but when technological progress began to change these capabilities considerably, European armies drifted apart. To take but two examples, by 1866, the Prussian army had introduced a breech-loading rifle capable of rapid fire at fairly short ranges - the famous Zündnadelgewehr System Dreyse -, while the Bavarian army still used a muzzle-loading rifle that, while suffering the disadvantages of all muzzle-loading infantry weapons, was effective at about twice the range of the Prussian rifle; the Bavarian gun was the not-quite-as-famous Podewils-Gewehr. Yet despite the very different characteristics of these and other weapons the Prussians never spent any efforts on creating “red” data lists for the Kriegsspiel, even if rules were regularly updated to represent the Prussian army at the time of publication. In a Kriegsspiel, it was always a Prussian army facing another Prussian army, which becomes understandable if one takes into account that it was primarily an exercise in decision-making.

The clearest indicator of the main aim of the Prussian Kriegsspiel however can be found in Jakob Meckel’s 1876 study on the Kriegsspiel, which clearly stated what the Kriegsspiel was first and foremost: an exercise in writing orders under the stress of battle. Its purpose was to expose participants to the chaos battle can create with regard to information flow and information processing, to force them to make decisions in such a chaos and to have them writing orders communicating their intensions to their imagined subordinates represented by the facilitators. Participants in a Kriegsspiel, Meckel stressed, would learn how to write their orders properly, ie in such a way that the recipient would understand what his superior wanted from him, and they would also learn how seemingly small errors could have massive consequences, or, as one participant of a recent Kriegsspiel run by the Conflict Simulation Group noted quite succinctly in the post-mortem: “It is rather helpful to spell the names of villages and other topographical features on the map correctly!” (something to which anyone who has seen batallions rush through the beautiful Downs to Iford Hill instead of Itford Hill can only agree).

A “modernized” Kriegsspiel?

It requires little explanation that information processing, decision making and communication remain, even 150 years later, as important as they were back in the days of Jakob Meckel, which is why Kriegsspiel-type wargames are today as relevant as they have been in the past. But if this way of running wargames is still of importance in principle, would it not be easier to have a “modernised” Kriegsspiel? This question really requires two answers on two quite different axes. Generally speaking one would answer with yes, as having a “modernised” Kriegsspiel is undoubtedly a very attractive proposition; it is for that reason that the Conflict Simulation Group is currently in the early stages of developing exactly that.

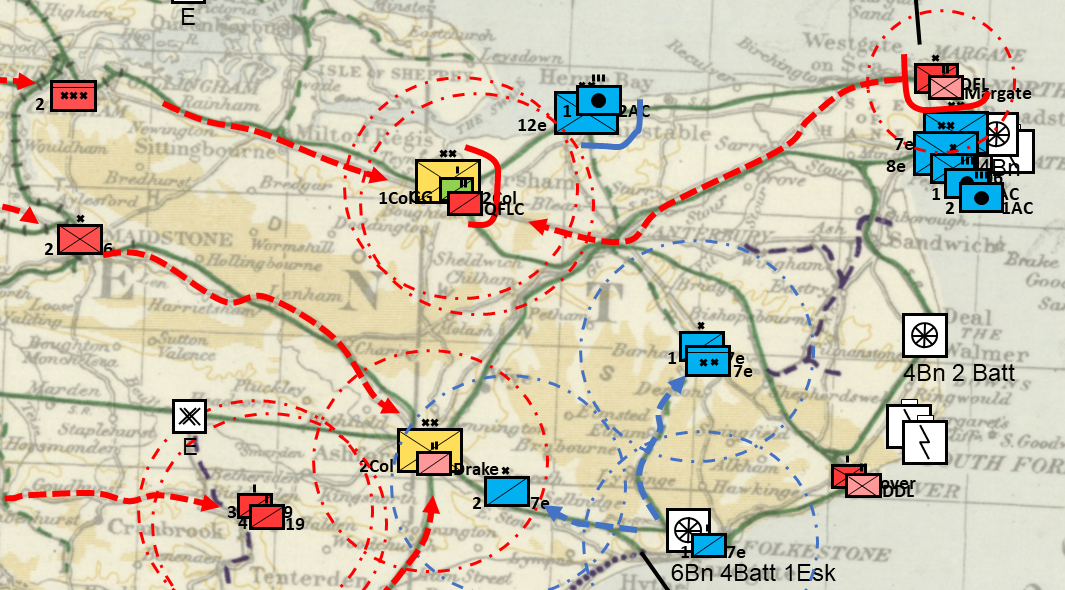

However, there is another side to the issue: the practical difficulties of developing and running such a Kriegsspiel are significant - and easy to underestimate. As noted above the Kriegsspiel is not about training the processing of information alone or the analysis of different types of information, it is about the problem of decision making based on an information gathering provess that may be flawed due to friction caused by combat. In order to do so a Kriegsspiel has to expose its participants to a real-time experience. While the facilitating team may well have a turn-based modus operandi (on the operation of a facilitating team see this blog entry, it is important to keep up the impression of real-time action for the participants; the feeling of slowly slipping behind events and therefore losing grasp of the situation is a crucial experience in a Kriegsspiel. While this is quite achievable with warfare that is two-dimensional at best, already the inclusion of air assets poses a significant challenge to the facilitating team; including cyber warfare is likely to exceed the capabilities of a normal facilitating team for processing all the relevant information in time. Unless significant digital resources are involved - which represent logistical challenges of their own - considerable personnel resourecs are required for the facilitating team, and even then running a Kriegsspiel in real-time would be a daunting proposition.

19th c. scenarios.

Of course, the key issue of decision-making under stress and influenced by friction can be observed throughout the history of armed conflict, with decision makers on an ancient battlefield just as likely to be bewildered by what was going on as those on an 21th c. one. So in theory one could run Kriesspiele based on scenarios from ancient, medieval or early modern conflicts, and with university students in history courses this can actually be quite worth the while. However, when it comes to military decision makers, experience has shown that the better participants can relate to the type of warfare depicted in the scenario, the better the overall experience, and hence the more successful the Kriegsspiel as a whole. Late 19th c. warfare offers the crucial advantage of already showing a significant amount of technological sophistication comparable to what would eventually be evident in World War I, with machine guns, barbed wire and heavy artillery all important elements of land warfare by the end of the century. While tactical and operational mobility still largely relies on infantry marching on foot and everything else being either mounted or horse-drawn, the function of each combat or combat support element is easy to explain, as they differ not fundamentally from their present-day equivalents; perhaps the only exception is cavalry, the use of which beyond reconnaissance usually requiring some additional explanation. And while 21st c. participants may not be as well versed in 19th c. battlefield tactics as their 19th c. counterparts had been, this lack of tactical understanding is not of great importance if the participants represent staff teams usually not involved in tactical minutiae (such as divisional staff teams), or if the *Kriegsspiel” is run totally on an operational level.

In all, then, there is still room for the Kriegsspiel even almost 200 years after its invention, provided one keeps in mind what its actual purpose is. For those running a Kriegsspiel it is important to communicate this purpose clearly to the participants so they realize that using 19th c. scenarios does not in fact diminish the Kriegsspiel’s usefulness. It is in fact first and foremost a matter of viability and of resources one is able to use for supporting a Kriegsspiel; 19th c. scenarios allow Kriegsspiele to be run with minimal logistical requirements.