How to run a Kriegsspiel – some brief notes.

by Jorit Wintjes

Introduction.

Many researching the history of the Kriegsspiel will probably have made similar experiences when encountering original 19th c. rules for the first time: a general puzzlement about how it all might have worked will have resulted in vague doubts about general accessibility setting in. This is very understandable and due to the general nature of these rulesets; after all, they were designed to be aids for facilitators who did not require much information about the general setup or running of a Kriegsspiel. Thus, rulesets usually provide only mechanisms for moving and fighting units and offer very little if any practical advice on how to set up and run a Kriegsspiel.

The purpose of these brief notes is therefore to provide some guidance for anyone trying to run a Kriegsspiel game. While they were written with the Conflict Simulation Group’s “Sussex Sorrows” in mind (for more information see the description on this page, they are in principle applicable to any kind of Kriegsspiel game. There is one important qualification: Kriegsspiele run by the Conflict Simulation Group are primarily run in educational contexts, and this educational approach is responsible for some of what is written below. To take but one example. if the main aim of the Kriegsspiel is not to educate but to entertain, running it in real time may not be as important as it is for educational purposes.

General Preparation.

One of the significant advantages of Kriegsspiel-type wargaming is that logistical requirements are minimal. Normally, one would divide participants into two teams red and blue which then form one or several staff teams depending on their respective size, and ideally have a room for each staff team. However, just having separate tables is fine as well if there is some sort of divider shielding the facilitators’ map from the participants.

Some effort, however, is required for the scenario design. Participants have to be provided with a general scenario overview, specific missions and order of battle sheets. Ideally, facilitators should also hand out sundry pieces of intelligence and information which add some colourful detail to the scenario. While not absolutely necessary for running a Kriegsspiel-type wargame, including such elements has shown to considerably increase immersion, which in turn results in a deeper experience for the participants. Example would be the inclusion of role-playing elements like biographical details for subordinate commanders as sketched out in the “Useful Idiots and Insufferable Geniuses” supplement to the “Sussex Sorrows” rules, or fictitious newspaper clipping commenting on events related to the scenario. The information pack should also include a copy of the map used by the facilitators; while it could be done in theory without, having the same points of reference on the map offers practical advantages for both participants and facilitators – unless not having these advantages is actually part of the Kriegsspiel, of course!

The Facilitating Team.

The Kriegsspiel will not work without a facilitating team, and the success of a game – in educational contexts this means a smooth running, exposing participants to friction and giving them food for thought - depends almost entirely on the facilitators. The size of the facilitating team depends on the number of participants, and it is advisable to err on the side of caution, ie to have rather more facilitators available than less. The facilitating team has to work as a team and under circumstances that can be hectic; usually, when things get stressful for participants, they are also for the facilitators. Within the facilitating team there are several roles to fill. Experience in running Kriegsspiele in educational contexts for almost a decade has resulted in the Conflict Simulation Group finding the following organization of the facilitating team most suitable to the task.

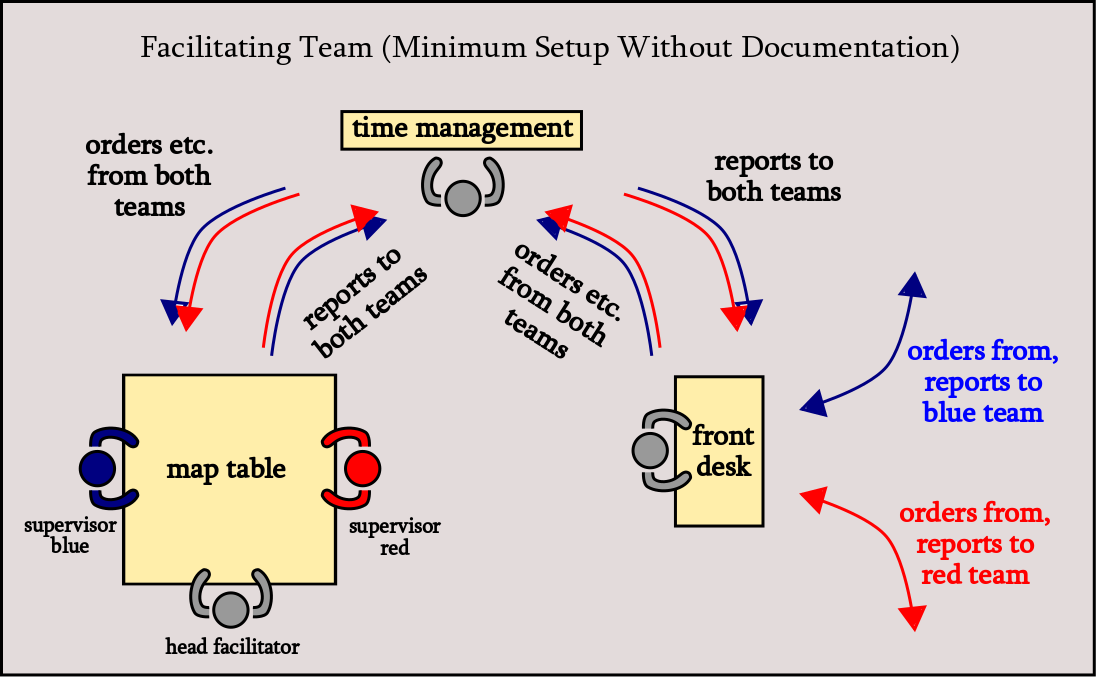

One or two head facilitators lead the facilitating team. They have to have a good command of the rules as they make the actual decisions, throw the dice and move the pieces on the map. They are in turn aided by a number of assisting facilitators, who serve in different functions. One assisting facilitator should be permanently assigned to each participant staff team as a ‘supervisor’. Staff team supervisors are tasked with writing reports exclusively for ‘their’ staff team and keep track of unit status, changes in capability due to losses in men and materiél and the like. Time management, which is a crucial element to running a Kriegsspiel and covered in a separate paragraph below, requires at least one assistant facilitator, while one or two should be assigned to a ‘front desk’, where participants drop off orders, and serve as messengers. Finally, for a post-mortem analysis, one further assistant facilitator should be assigned to keeping a communications and battle log, and to making photos. For a mid-to-late 19th c. scenario pitting two divisions against each other – with staff teams of 4-7 participants each – this means a facilitating team would require at the very least four assistant facilitators in addition to the one or two in charge of running the game.

A Crucial Element – Communications Delay Management.

Kriegsspiel type wargames excel at exposing participants to fog-of-war situations. However, the effect is considerably diluted when the game is run such a way that participants have more time at hand for evaluating information and making decisions as they would have in reality. Of course, running a game truly in real-time is impossible, but what is possible and indeed imperative, at least in educational contexts, is to provide participants with a real-time experience.

In order to achieve this, communications delay management is crucial; the facilitating team has to keep track of when orders from the staff teams come in, when these orders will actually reach their units and how long it takes to answer these. By tracking the process of orders and reports and handing them to the recipients with a certain delay, an atmosphere of information incompleteness is created that is crucial to the overall Kriegsspiel experience. Delayed communications and the necessity of operating on the basis of incomplete information exposes participants in a Kriegsspiel to one of the more unsettling aspects of military decision making, and one that is in the age of modern communications technology still as relevant as it was in the age of the mounted messenger – as orders and reports still require time to be composed, read, understood and passed on to subordinates.

Integrating proper communications delay management in a Kriegsspiel comes at a price. While in very small scenarios involving only one participant on each side a facilitator might be able to keep track of orders and reports, this quickly becomes impossible in larger scenarios due to the sheer volume of orders and reports generated throughout a game. The best solution here is to assign at least one assistant facilitator to managing communications delay; for that purpose, the Conflict Simulation Group uses timelines on whiteboards. The assistant facilitator charged with communications delay assesses how long orders and reports will take to reach their intended recipients, pins the message to the time on timeline when it will reach its destination, to be removed for further processing once that time has been reached.

To give an example, assuming a cavalry regiment reports back to divisional HQ about an enemy they spotted. The report is generated by the assistant facilitator supervising the division as soon as the cavalry spots the enemy. The supervisor then calculates how long it will take for the report to reach divisional HQ – for example 30 minutes – and hands the report to the assistant facilitator responsible for communications delay management, who will keep track of the time by pinning the report to a whiteboard with the timeline on it, and hand it over to the front desk once the 30 minutes are over; the assistant facilitators running the front desk will then hand over the report to the staff team. In this way it is ensured that reports will reach the intended recipients with a realistic delay, resulting in the need for participants to wrestle with the ghastly problem of reports reaching them that may be hopelessly outdated. The schematic below illustrates the flow of information in a typical Kriegsspiel-type wargame.

In case documentation of communication throughout the game is desired, any in- and outgoing communication has to pass through the hands of the assistant facilitator tasked with documentation. Experience has shown that for communication from the map table to the participants this is best done before it is fed into the time management system, while for communication from the participants to the map table it is best documented before it is handed over to the supervisors on the map table. The illustration below shows the inclusion of documentation in the workflow of the facilitating team.

Getting Started.

Ideally, participants in a Kriegsspiel-type wargame will have had access to the scenario information a few days in advance and launch into the game with a well-prepared plan, so that the – equally well-prepared – facilitator team can hit the ground running. In educational contexts however this is often impossible to achieve – and in any case not necessary. Experience has shown that it is sufficient to allow for 90-120 minutes preparation on the day of the Kriegsspiel, during which the participants digest the information provided to them, while the assistant facilitators are briefed on their role; it is advisable to have a ‘practice run’ for for facilitating team during which the team goes through the process of receiving orders, creating reports and time management.

General Course of Action.

Real-time is all-important, as was noted above. Of course, for the facilitators it is impossible to run the wargame in real time. Experience from Kriegsspiel-type wargames run by the Conflict Simulation Group has shown that depending on the scenario, taking steps – intentionally avoiding the term “turn” here! – of 10 to 30 minutes is quite useful, depending on the nature of a scenario. A tactical scenario may warrant fairly small steps of 10 to 15 minutes, while a large operational or theatre level wargame may work well with steps of 30 minutes. Flexibility is the key here: depending on how a given situation develops it may be necessary to switch for some time to smaller steps. It is advisable to always keep the same sequence when working through the map during each step, for example beginning in one corner of the map and then going through all units clockwise or anti-clockwise.

As the staff teams formed by the participants represent staffs that are usually present on the map as well it is possible to show them what they would actually see in real life from time to time. This can be easily done by taking pictures of those portions of the map covering what is within their view; it is advisable, though, to use this instrument sparingly.

The Facilitators’ Prerogative - Making Decisions.

Once it has started, units will begin to move and eventually make contact. It is really only at that point that the rules become necessary, as they provide the relevant mechanisms for resolving conflict. Contact between two opposing forces is a mixed blessing for the facilitator team: on the one hand it significantly increases the workload, on the other hand, as simple mechanisms allow for resolving quickly an engagement that in real life might last 30 Minutes or more, contact can actually free time for the facilitating team to write reports.

When it comes to combat experience has shown that there is a certain urge, particularly among less experienced facilitators, to immediately relate the results of an action to the participators, including detailed reports on friendly and enemy losses. It is advisable to resist this temptation, however, as in real life combat would not result in local commanders instantly aware of the situation once bullets stop flying. When in doubt, it is better to delay reporting back to the participants for a few more minutes to simulate the chaos on the ground that may be the result of an action.

It should be stressed that providing a real-time experience for the participants should have the highest priority for the facilitators. Situations may arise when facilitators can no longer run the game with the necessary speed while strictly adhering to all rules. In such a situation, keeping up the real-time experience should always take precedence over sticking to rules details; facilitators should have no qualms about simplifying the rules to keep the game running at speed.

Post-Mortem.

At some point the facilitators will decide to call it a day, usually when something decisive has happened. The time required by the facilitating team for preparing the post-mortem will then depend on deep various aspects of the game should be covered. All post-mortems will include a brief review of the respective plans and an overview over the action; taking a closer look at the communication can also be very instructive but requires at least a cursory overview over the orders and reports processed during the game, which can take some time. Even so experience has shown that the post-mortem should follow the actual game as soon as possible; depending on the time available and the depth intended one can always continue the discussion on another day, but an initial overview over plans and action should be presented with memories of all participants still fresh.

A Final Remark.

Running a Kriegsspiel as outlined above requires some effort by the facilitators, particularly when more than a handful of participants are involved. Against this, however, has to be balanced the fact that the actual logistics required are minimal – some sort of accommodation arrangement, sheets of paper and maps; while tokens certainly add to the visual impact of a game, they are strictly speaking not necessary, as one could just as well simply write onto the maps. First-time facilitators might find the learning curve a bit steep, but according to the Conflict Simulation Group’s experience routine will set in quickly, particularly if one begins with scenarios not requiring tactical detail work; for exposing participants and facilitators to the Kriegsspiel, operational level scenarios may be a good starting point. The Conflict Simulation Group can only encourage everybody out there to give it a try!