Conflict simulation in the classroom

For the past ten years the Conflict Simulation Group has developed conflict simulations for a wide range of applications in academic education and employed them in class. They range from simple, small-scale simulations designed to illustrate a specific aspect of a political or military conflict of the past to large and complex simulations aimed at providing participants with some experience of various general issues related to political and military decision making. These participants usually are either students in our Digital Humanities and History programs or military officers and officer candidates. Below are brief descriptions of the three simulations directly based on the Prussian Kriegsspiel currently in use ; descriptions of other simulations will follow soon.

At present, the Conflict Simulation Group regularly runs three different Kriegsspiel-type simulations.

1. The “traditional” Prussian Kriegsspiel.

The Conflict Simulation Group runs Kriegsspiele using the rules published by Wilhelm von Tschischwitz in 1867; it was this set of rules that started wargaming in the anglophone world when it was acquired by the British in 1872, and it is closest to the map the Conflict Simulation Group uses, an 1867 map of the Battlefield of Königgrätz, which is one of the very few Kriegsspiel maps still extant. Scenarios are usually of a strictly tactical nature, with very little non-kinetic happening in the battlespace; this is due to the original Kriegsspiel rules mostly ignoring issues of logistics, casualty management or civil-military interaction, concentrating instead on tactical decision making. Scenarios will invariably be based on the actual Battle of Königgrätz; while in theory, the whole battle could be simulated, the realities of logistics (in particular the number of available facilitators) usually restrict scenarios to up to one or two army corps on each side, with participants divided up into divisional and corps staff teams.

In running the “traditional” Kriegsspiel, the Conflict Simulation Group follows three key ground rules:

High Accessibility - The participants do not have to learn the rules; instead, they can concentrate on making their plans, processing information and making decisions.

Realtime - While the facilitators will to a certain extent use turn-based mechanisms, it is crucial for the participants to experience the course of the simulation in real time. This not only considerably benefits immersion, it can also add considerably to the stress experienced by participants as periods of inactivity can be followed by hectic activity. Perhaps even more important, running the Kriegsspiel in quasi-realtime rewards those participants who try to keep up a high operational tempo.

Consequence - Once underway, the simulation will not stop to address mistakes made by the participants. It is one of the key objectives of the Kriegsspiel to confront the participants with the results of failure, and if questionable decisions, slow operational tempo or other factors cause plans to unravel, then participants will have to deal with it.

2. The Meckel Kriegsspiel.

The Conflict Simulation Group also regularly runs Kriegsspiele based on the rules published in 1875 by Jakob Meckel, the Kriegsspiel’s greatest theoretician. He introduced the distinction of tactical, operational and strategic Kriegsspiele (“strategic” in the usage of the time meaning a theatre-level wargame), and from the 1880s onwards operational Kriegsspiele became quite common in German armies; surviving records show that the Bavarian army for example regularly ran one large-scale operational wargame each summer, usually involving all of the Bavarian army.

The Conflict Simulation Group has developed a three-tier simulation system that closely follows Meckel’s ideas and consists of three different simulations all built around the same basic combat resolution mechanism: the tactical simulation “Doom of Eastbourne”, the operational simulation “Sussex Sorrows” and the strategic (ie theatre-level) simulation “Twelve Days to London”. The simulations can be run on actual maps as well as virtually, with the facilitators working on digitizd versions of contemporary topographical maps.

All three simulations are based on the same scenario, a French invasion in Britain in 1883. While this may seem to be rather outlandish at first, it is in fact a nod to the very first wargames run by the British army in the early 1870s - which routinely saw a “blue” army invading Britain and a “red” army defending the realm. The fear of invasion was at the time not confined to military circles, as several “invasion scares” in the late 19th c. as well as hundreds of literary (or semi-literary) texts covering such invasions published between 1871 and 1914 show. Also, using a pre-World War I scenario eases the workload of the facilitators considerably, as conflict is still fundamentally a two-dimensional affair, yet it is still close enough to the realities of modern warfare so that no lengthy historical introduction is required.

All three simulatons also share the inclusion of role-playing elements. Participants will find brief biographical information on their subordinate commanders in their briefing material, allowing the facilitators a certain amount of leeway when it comes to executing orders and reporting back. Experience has shown that the impact of the actual character of these subordinate commanders can be nothing short of dramatic (with a capital D…).

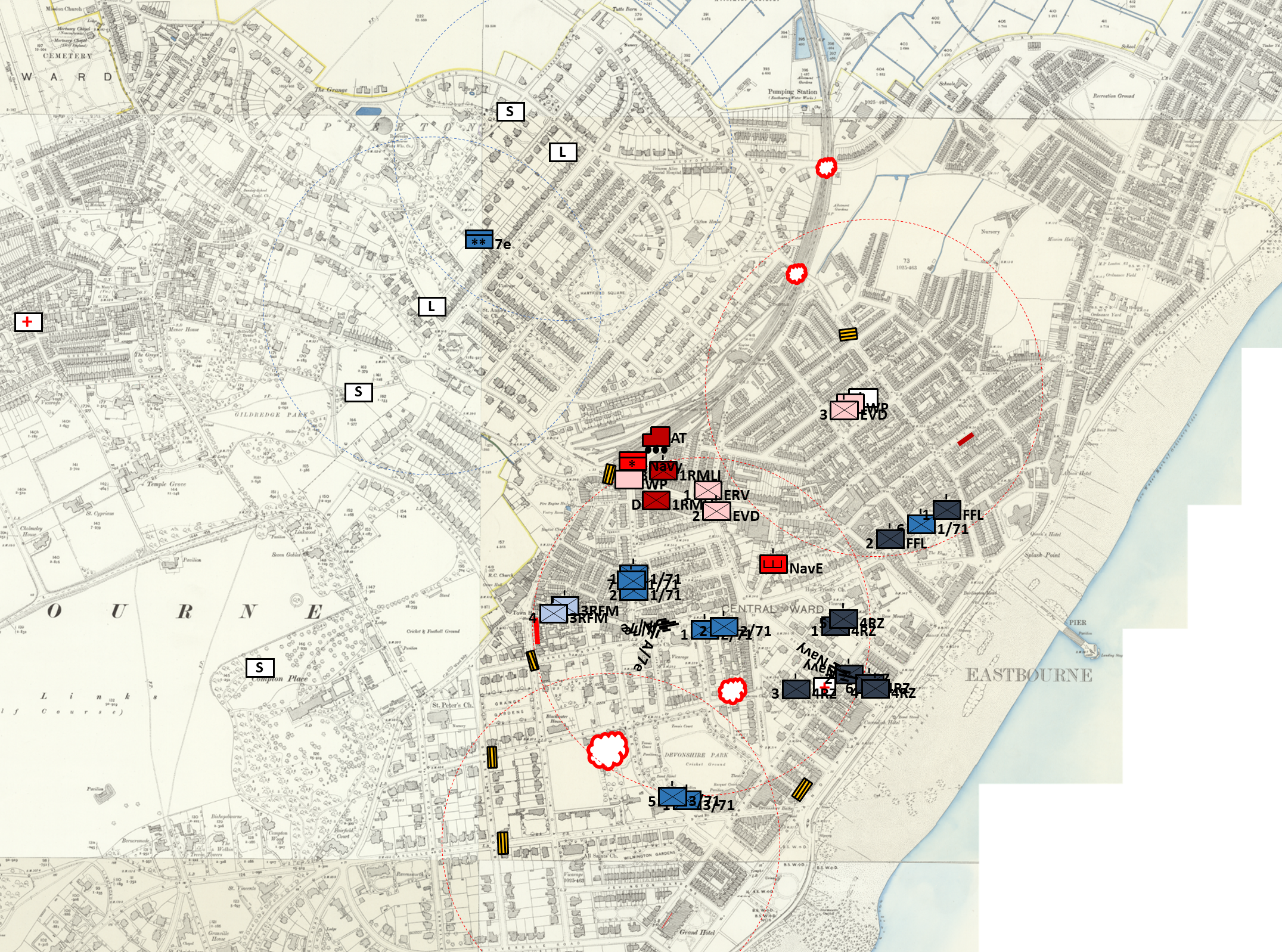

“Doom of Eastbourne” is a tactical simulation covering the defence of the lovely English seaside town of Eastbourne against a French attacker.

After five hours of intense fighting, the defenders still cling to the railway station, but barely

It normally has two teams of 3-6 participants facing each other and runs over 3-6 hours. It includes some logistics and casualty management elements, but has only limited civil-military interaction elements.

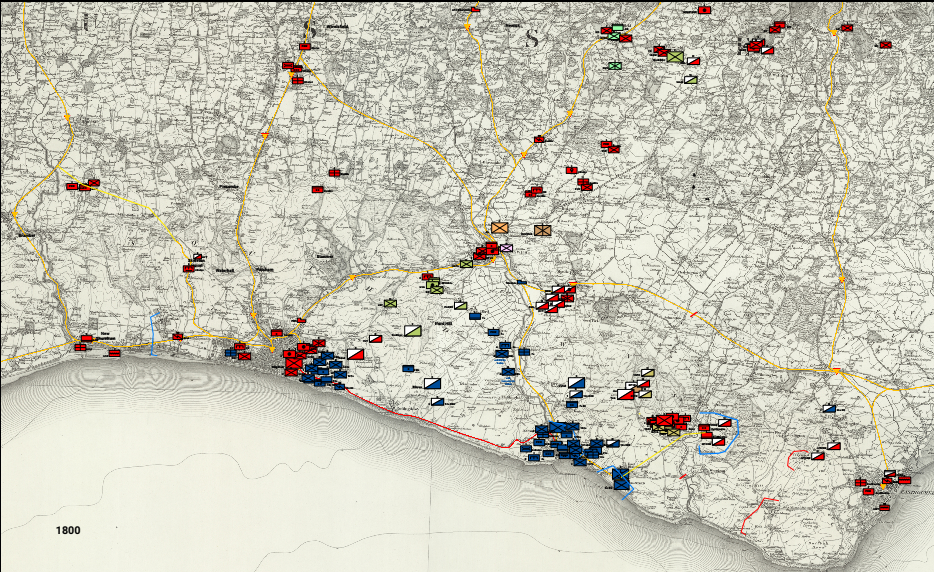

“Sussex Sorrows” is an operational simulation covering the attempt of a French force to expand its bridgehead in Southern England. It usually has ten teams of 3-6 participants facing each other, with each side consisting of one army corps team and four divisional command teams. Participants not only have to manage their subordinate forces but also coordinate their internal communication, which, as experience has shown time and again, can rapidly become a major issue.

French bridgehead collapsing after three days of heavy fighting

“Sussex Sorrows” covers a space of 40km by 70km and features both logistics and casualty management elements as well as civil-military interaction which, depending on the decisions of the participants, can provide a considerable amount of distraction. “Sussex Sorrows” is usually designed as a three-day real-time simulation (running either on three consecutive days or on three weekends allowing participants more time to fully digest the chaos they have created on each day).

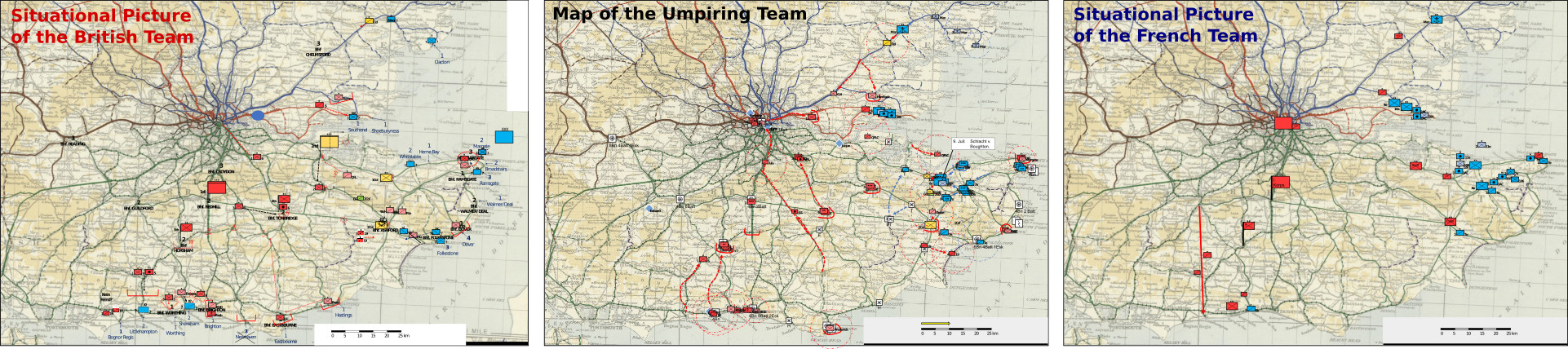

“Twelve Days to London” is a theatre-level simulation covering a French invasion which aims at occupying London within twelve Days from the first forces hitting the beach; it includes elements of logistics, casualty management, civil-military interaction as well as espionage.

It usually has two teams of 4-8 participants facing each other and runs over twelve consecutive days; for reasons of practicability it is the only simulation run by the Conflict Simulation Group that is not run in real time - participants send in their orders for the next day until 2359, the facilitators then execute these orders, prepare reports and other materials until 1800 on the following day, which then leaves the participants about six hours to go through the material and write new orders. For more on “Twelve Days to London” see the Blog.

3. Pluie de Balles - The “gamified” Kriegsspiel.

On of the main drawbacks of the Prussian Kriegsspiel is the simple fact that the facilitators usually try to do their best to keep the simulation running. While this sounds like a blindingly obvious fact, it is actually a major problem: as the faciliators in the Prussian Kriegsspiel represent all levels of command below that of the participants, the latter effectively have subordinates that will always, and without question, execute orders as quickly and as efficiently as possible. While the introduction of role-playing elements can counter this tendency to a certain extent, it is still all but impossible to depict subordinates who simply ignore direct orders - yet these things can happen and do happen in war, for a variety of reasons.

The largest and most complex simulation currently employed by the Conflict Simulation Group addresses this problem by replacing the facilitators with more participants, who move around forces on large maps using simple tabletop mechanisms, while other participants sit in staff rooms eagerly awaiting reports from their subordinates - who have to balance the need of controlling their forces and of writing reports back to their taff. Pluie de Balles exposes the participants to some of the friction that is caused by having to process information, make decisions and communicate under stress, as well as to test the limits of the participants’ capability of working together as a team. Pluie de Balls, which is also based on late 19th c. invasion scenarios, is run on a regular basis with groups of up to 40 or more participants from both a civilian and a military background. Participants regularly describe their experiences as highly illuminating though, due to the considerable stress involved, not always exactly enjoyable.

The rule set is inspired by the historical Prussian Kriegsspiel and designed with scalability in mind. It allows for 2-3 umpires to easily accommodate 40 participants or more, of which about a third will have an experience very similar to that of the original Prussian Kriegsspiel. The remaining participants require some basic knowledge of the rules and game mechanics, easily provided during the time required for the others to develop their operational plan. A brief overview over Pluie de Balles and its purpose can be found in the publication Pluie de Balles - complex wargames in the classroom.