Kriegsspieler of the Month - Ernst Heinrich Dannhauer (1800 - 1884)

by Jorit Wintjes

With this month’s Kriegsspieler we turn to the circle of friends around Reisswitz in which the Kriegsspiel was originally developed. Reisswitz himself mentions three fellow officers in the preface to the Kriegsspiel publication, Gustav von Griesheim, Karl Friedrich von Vincke and Ernst Heinrich Dannhauer. While these three formed something that might be called an inner circle, other officers were associated with that first group of Kriegsspielers as well, including Helmuth von Moltke. During the following month we will take a closer look at these associates of Reisswitz, many of whom had either long and successful military careers or biographies that were in other ways colourful and interesting. This month’s Kriegsspieler, Ernst Heinrich Dannhauer, falls squarely into the first category; entering the Prussian army at the age of 16 he served for almost 50 years, retiring as lieutenant general. Among those with an interest in the history of the Prussian Kriegsspiel he is mostly known for a brief article written in 1874 in which he outlined how the Kriegsspiel gained official attention; as mentioned last month Dannhauer’s article is the main source for Reisswitz’ activities in Berlin. It will be shown below that his importance went in fact beyond being a key witness for the history of the early Kriegsspiel.

Born in 1800 as the son of a Prussian tax official, Ernst Heinrich Dannhauer attended the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Gymnasium in Neu-Ruppin from 1808-1815; he seems to have enjoyed his time there and kept contact with his old school, sending a congratulatory letter on the occasion of its 500th anniversary in 1865; the school apparently kept a collection of letters Dannhauer had sent over the years in its archive. In 1816 he then joined the Prussian army as a gunner, serving with the guards artillery brigade. After two years at the Vereinigte Artillerie- und Ingenieurschule (the Prussian army’s main school for artillery and engineer officers), during which he gained his commission as lieutenant, he re-joined the guards artillery brigade in 1819 at the very time Reisswitz was transferred to Berlin. It is perhaps not surprising that both officers, who evidently had a keen interest in their trade as is evidenced by the older Reisswitz being posted to the Artillerie-Prüfkommission, while the younger Dannhauer became a teacher at the Guards Brigade School in 1827, took to each other. Going by his recollections published in 1874, Reisswitz left a considerable impression on the younger Dannhauer; however, the latter was also clearly valued by Reisswitz as he thanked him in the preface to the publication of the 1824 rules.

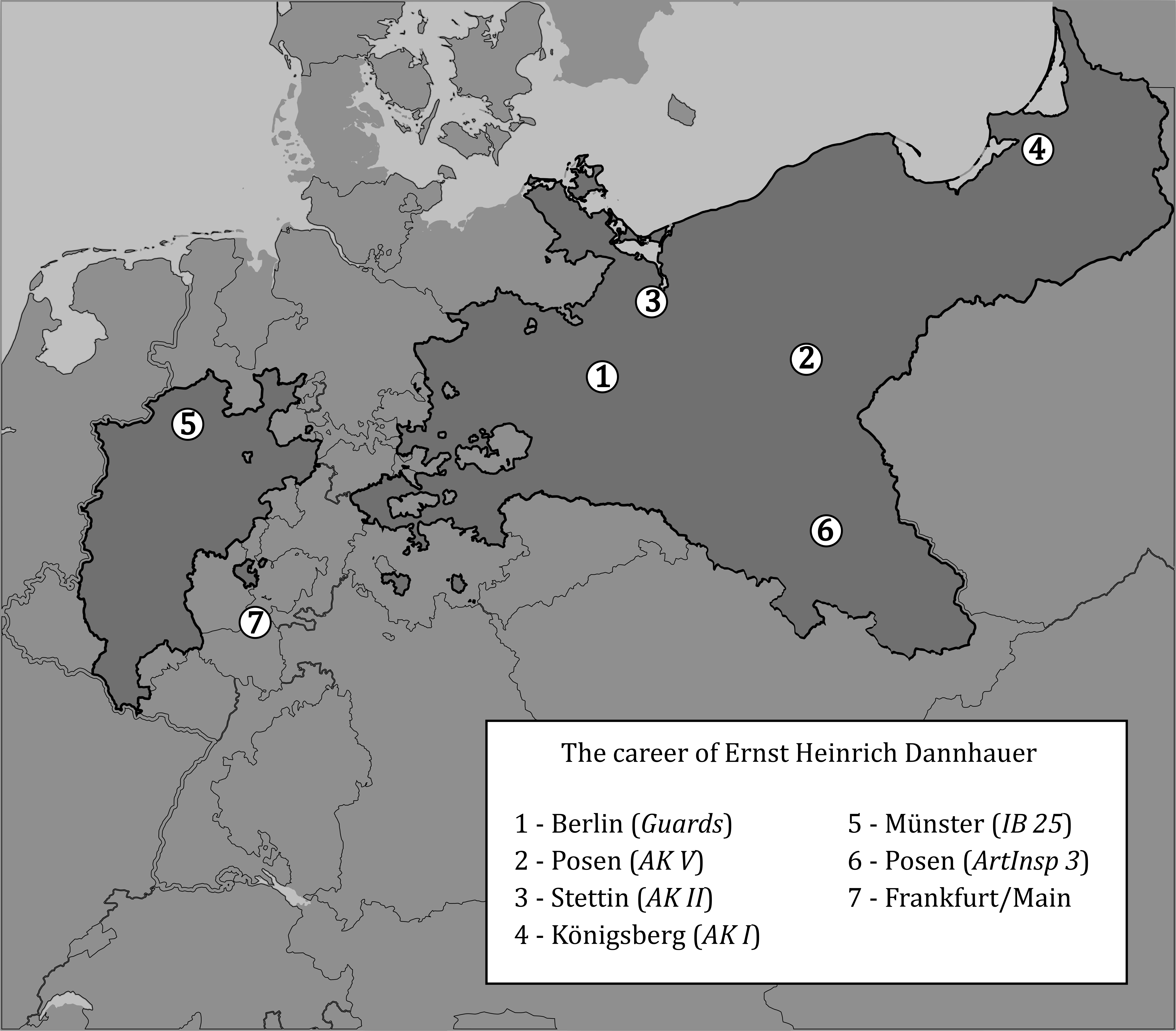

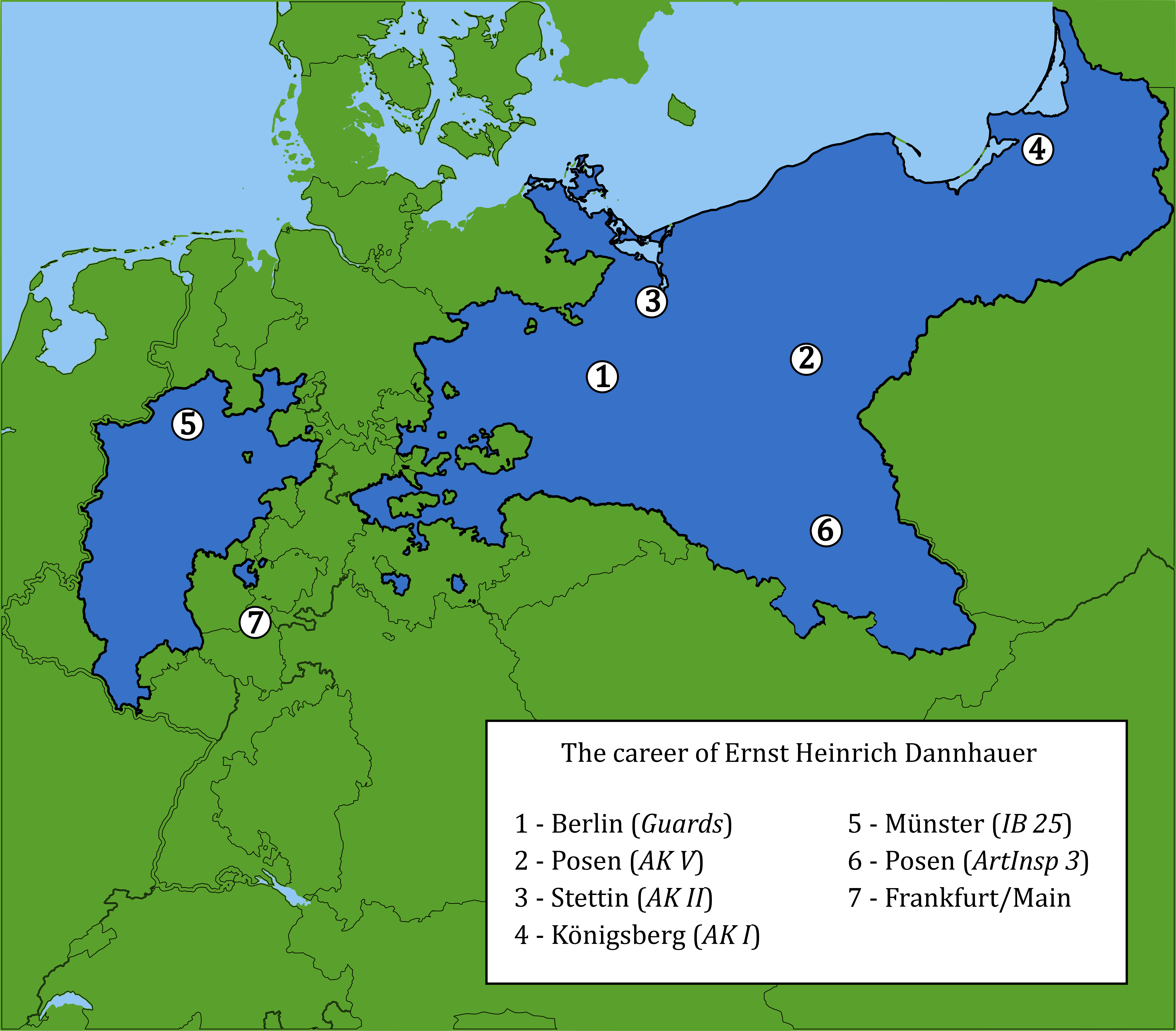

Dannhauer would stay with the Berlin garrison until promoted captain in 1833, when he was transferred to the staff of Fifth Army Corps in Posen. After further staff service with Second Army Corps in Stettin and First Army Corps in Königsberg and promotion to major in 1841 he was finally appointed chief of staff of the Königsberg army corps in 1846. He served for almost a decade in Königsberg and was apparently instrumental in establishing the use of the Kriegsspiel there. When he left Königsberg in 1855 for his first major command over 25th Infantry Brigade at Münster, he donated a number of wargaming maps prepared by himself to the Königsberg garrison. Decades later the garrison was apparently still famous for its collection of Kriegsspiel maps, and it is hardly a coincidence that Julius von Verdy du Vernois, who served as chief of staff at Königsberg in the early 1870s, became an important Kriegsspiel theoretician who will feature in a future instalment of Kriegsspieler of the Month. Dannhauer had, or so it seems, had established Königsberg firmly on the Kriegsspiel map, or rather the Kriegsspieler map.

Promoted to major general in 1855 he held command over 25th Infantry Brigade for about two years. In 1857 he left Münster for Breslau to take command over 3. Artillerieinspektion (the parent unit of 5. and 6. Artilleriebrigade). After less than a year in Breslau he was posted to the Bundes-Militärinspektion, a commission of high-ranking officers from the larger member states of the German confederation, which was based at Frankfurt. Dannhauer now entered the treacherous seas of German politics of the 1850s, dominated by the ever-increasing conflict between Prussia and Austria over hegemony in German-speaking central Europe. While Dannhauer’s political convictions are unknown, his actions as a member of the commission put him on a collision course with BIsmarck and resulted in the “Dannhauer case” (“der Fall Dannhauer”) becoming a minor episode in the iron chancellor’s biography.

Among the commission’s duties was the inspection of the Bundesfestungen, the fortresses manned by forces of the German confederation. On one of these inspections Dannhauer and his Austrian colleague Joseph Ritter von Schmerling apparently found the state of the fortresses they inspected considerably lacking. Dannhauer seems to have got along with his Austrian colleague fairly well, and they worked out a draft resolution asking for substantial financial sums in order to improve the state of the Bundesfestungen. Dannhauer put his signature under the draft without first consulting with Bismarck, the Prussian envoy to the diet of the German confederation, or indeed the Prussian government. Bismarck himself was not amused, all the more so as he suspected an Austrian plot behind the whole affair. While the Prussian foreign minister von Schleinitz in the end reminded Dannhauer not to agree to any Austrian suggestions without expressive consent by the Prussian government, Dannhauer’s career was apparently unaffected by it all. After the affair he was promoted lieutenant general in 1859 and was in charge of the Bundestruppen in Frankfurt from 1863 to 1866. He finally retired from service in March 1866 after nearly 50 years of service.

Dannhauer’s importance for the history of the Kriegsspiel is twofold: it has already been mentioned that he is a key witness for the early history of the Prussian Kriegsspiel, and without his testimony the events of 1824 would lie nearly totally in the dark. However, of equal importance was his actual activities as a Kriegsspieler. Evidently, he did not give up using the Kriegsspiel once he had left Berlin but brought it to his new postings, and once in Königsberg he seems to have been responsible for establishing the Kriegspiel there. Dannhauer is thus a good example for how the Kriegsspiel managed to overcome initial opposition in the early decades of its history - by having enthusiastic Kriegsspielers inspiring others to join them in their activities.

At present there is no in-depth study of Dannhauer’s biography extant, nor is there a good overview available. However, while no papers appear to have survived, there is sufficient published material from his time in Frankfurt to gain some insights into his activities there, and a more comprehensive study of his biography would definitely be worth the while.

So much for this month’s Kriegsspieler. Next month we will look at Karl Friedrich von Vincke, another member of the circle of friends around Reisswitz, who shared the experience of getting in the way of Bismarck with Dannhauer - only that in the case of Vincke this was not confined to commission work but involved an actual duel! For more on him see next month’s installment of Kriegsspieler of the Month.