Drama in Liverpool! A large game of Pluie de Balles.

by Jorit Wintjes

I. Introduction.

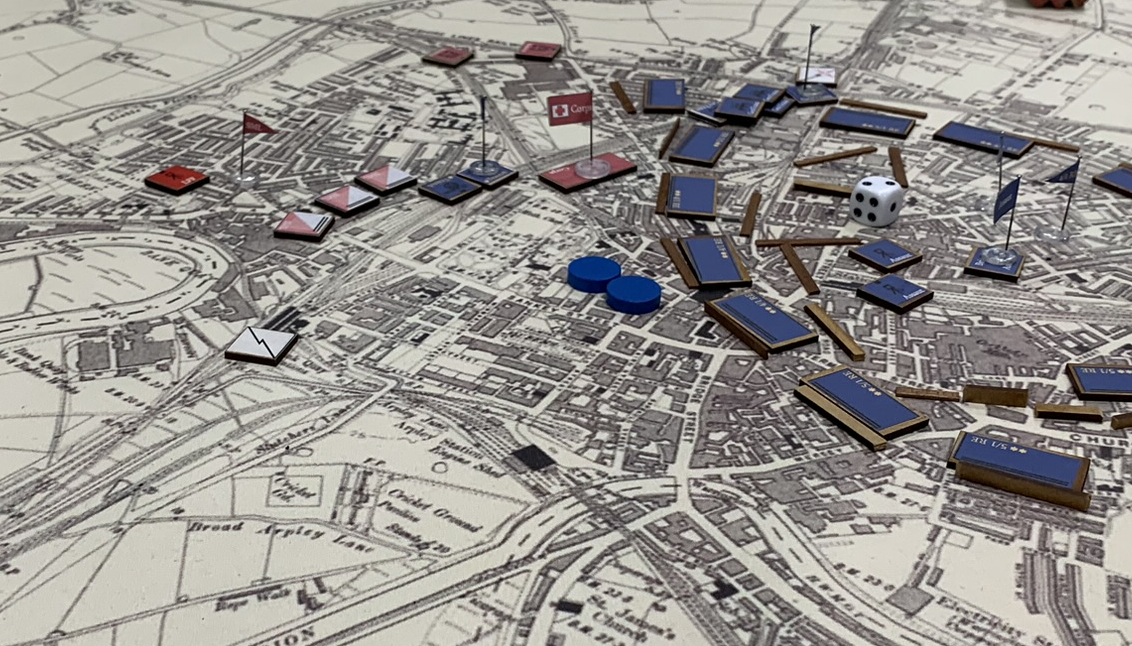

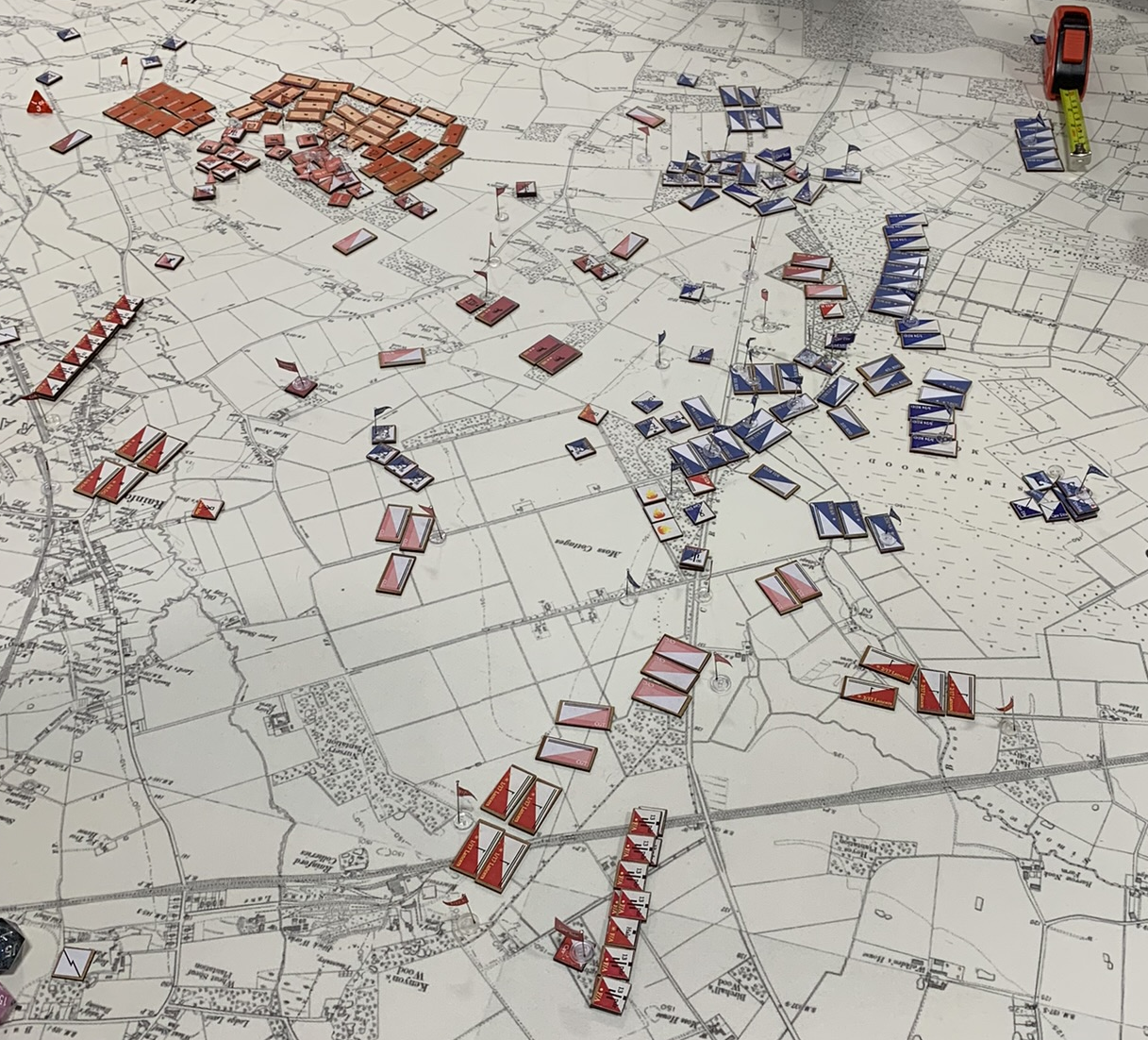

February saw another big Pluie de Balles game at Helmut-Schmidt-Universität Hamburg, with around 40 participants divided up into to unequal groups of about 25 and about 15 to form French and British teams. The scenario used was the standard Liverpool scenario which the Conflict Simulation Group has run several times; reports of other games based on this scenario can be found in the blog section of this page.

This time however there were four key differences which had quite an impact on the overall outcome: first, the Liverpool map was enlarged by about one third, allowing for more room north of St Helens and putting that town more towards the centre of the map;

fig. 1: the enlarged Liverpool map

fig. 1: the enlarged Liverpool map

then, managing civilians was one of the challenges force commanders faced. Civilians were represented on the maps with specific tokens, and each side could move them following simple rules; groups of civilians had just one capability - preventing any unites from rapidly moving through them - which made moving them out of the way and off the main axes of advance quite important; thirdly, off-map action was introduced: both teams had to plan their reinforcements by deciding which elements to put into which ship or train, and both sides could allocate assets to intercept enemy reinforcements and guard their own; and finally, to further increase the workload of the staff teams, VIP missions were introduced on the second day, which were designed to throw them slightly off track and force them to allocate ressources to the fulfilment of these missions.

The result was a game that was more dramatic than most!

II. Force Composition.

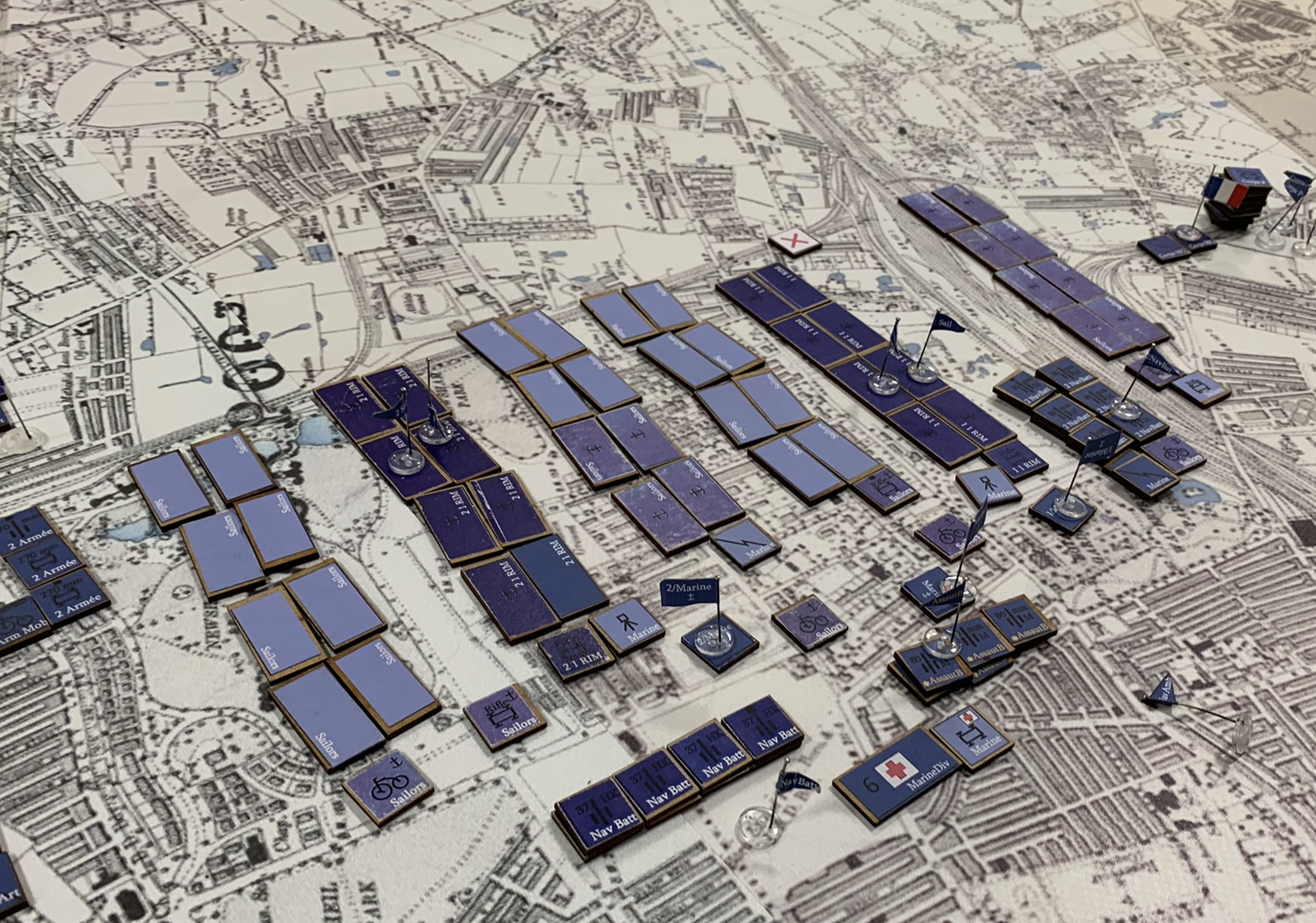

Force composition differed somewhat from earlier scenarios. On the French side, 4e Corps had two infantry divisions on strength with 13 battalions of infantry and four batteries of 90mm field guns each. In addition, a division formed from two navy brigades with three battalions each, a battery of 37mm Hotchkiss guns and one of 80mm mountain guns as well as a cavalry division with 16 squadrons of cavalry and four batteries of 90mm horse artillery were available for supporting the corps’ operations. Further support was available in four batteries of heavy and superheavy artillery totalling eight 120mm guns, four 220mm mortars, three 240mm guns and one 270mm mortar; also, the navy had managed to transfer a superheavy railway gun (340mm) into theatre, which was available as well. Directly under the control of Corps HQ was a regiment of infantry with three battalions, a small experimental brigade of bicycle infantry with two battalions and another experimental brigade of two battalions which were specifically trained to quickly entrain and detrain. For the following day an experienced brigade of Zouaves, another experienced brigade of Algerian Tirailleurs and an elite cavalry brigade were available as reinforcements. However, these reinforcements had to be shipped into Liverpool, and in theory the British could try to intercept French transport ships with torpedo boats. Against these, the French navy had provided three gunboats, which could either be used in support of ground forces in the Liverpool and Birkenhead region or for guarding the transports against attacks by torpedo boats. In all, 4e Corps had quite formidable forces at its disposal which included 48 battalions of infantry, 14 batteries of field artillery of various types, four batteries of heavy artillery and 24 squadrons of cavalry.

Pitted against 4e Corps was the Liverpool Field Force, which was built around two divisions, both of which were not at full strength on the first day. 5 Division composed of two infantry brigades with a total of nine battalions had on the first day only the five battalions of 1/5 Brigade available, while Colonial Division, a unit composed of various Australian and Canadian units put together in a brigade of mounted infantry and one of cavalry, had only four battalions of mounted infantry supported by two batteries of horse artillery available on day one. Both units had reached Warrington during the night and had their starting positions near the railway line immediately north of the city. Liverpool Field Force HQ also had a number of independent brigades on strength; these included a powerful navy brigade of two battalions of Royal Naval Light Infantry supported by four field and seven heavy guns, an equally powerful Highland brigade of four battalions supported by a battery of field artillery, a battery of heavy artillery and a number of railway guns, an understrength volunteer brigade of two understrength battalions, a battery of field artillery and a small cavalry element, another volunteer brigade of similar strength but with better equipment, a third volunteer brigade composed of highly experienced Bonapartist exiles and a volunteer cavalry brigade mostly made up of local gentry and their tenants and armed with shotguns. Also, a number of armoured trains and two superheavy railway guns were available as fire support, as were six torpedo boats which could either used to attack French ships supporting French land forces or to intercept French reinforcements. For the second day trains were supposed to reach Warrington carrying the remaining brigades of 5 Division and Colonial Division, a crack cavalry brigade and another infantry brigade of four infantry battalions. Overall, British forces included 29 battalions of infantry, some of which were at only 50-60% strength, 19 batteries of field artillery of various types and four heavy batteries, and 25 squadrons of cavalry.

III. Plans, good ones, actually.

Both sides made comprehensive and plausible plans.

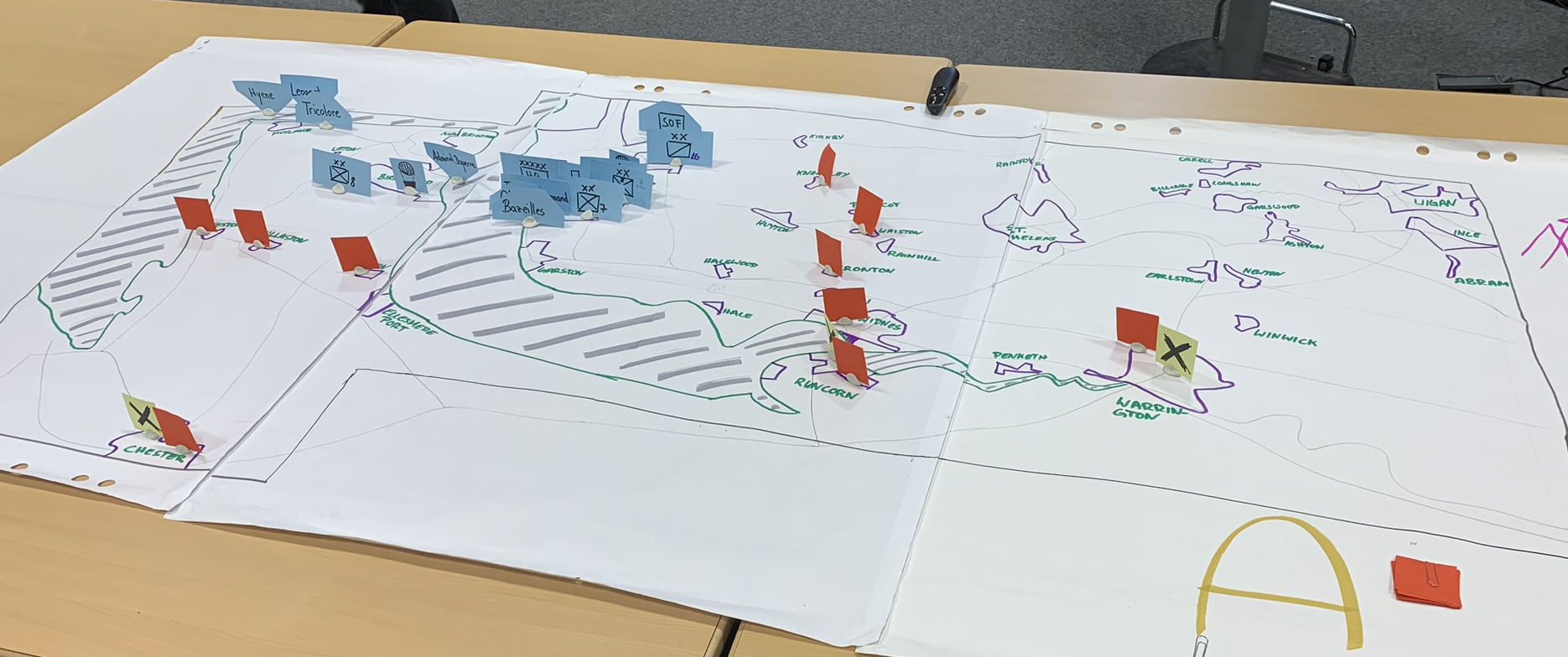

fig. 2: French staff map showing initial dispositions.

fig. 2: French staff map showing initial dispositions.

The French decided to put one division on the Wirral Peninsula with a defensive mission, holding the krey ground north of Birkenhead which controlled the access to Liverpool harbour, while the bulk of 4e Corps was committed to the Liverpool area, where the other infantry division was to push quickly to Widnes, securing the bridge at Runcornn Gap if possible.

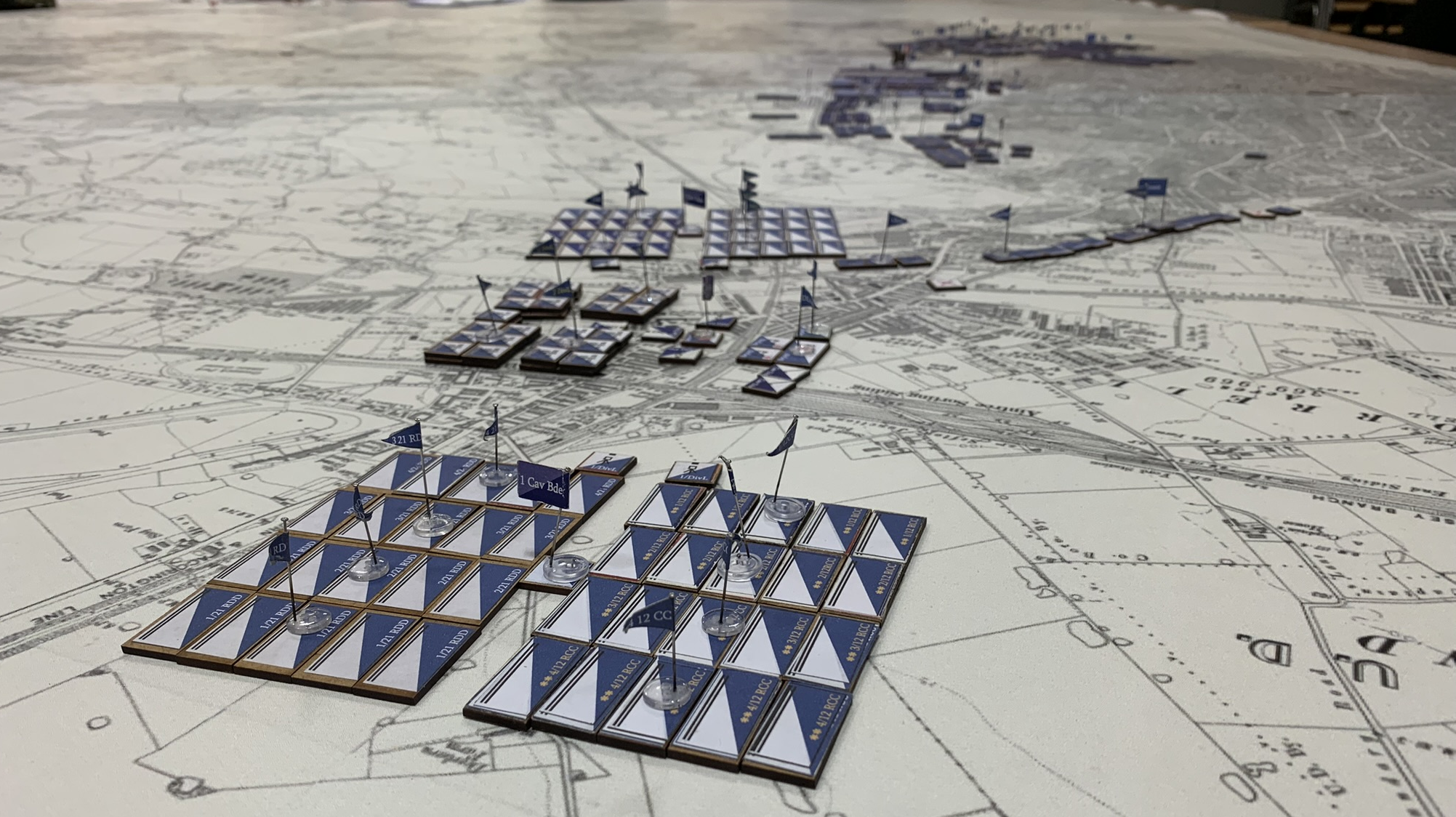

fig. 3: French forces in Liverpool, cavalry division in the foreground.

fig. 3: French forces in Liverpool, cavalry division in the foreground.

The naval and cavalry divisions were to cover the attacking division’s flank, while the heavy artillery was to support the attack.

fig. 4: French naval division.

fig. 4: French naval division.

The experimental railway brigade was given a special mission: it was to try to push through enemy lines well to then north of Widnes and get into the enemy rear to attack targets of opportunity. Once reinforcements had arrived, they were to be used to continue the attack towards Warrington and, if possible, to push southwards from Birkenhead towards the main British logistics hub at Chester.

The British plan, as the staff team had correctly assumed to be facing considerable odds, stressed that day one would be characterized by a bitter struggle for survival. They were - at least initially - confident to hold their positions in Widnes, which was defended by the naval brigade; 1/5 Division, the Australian mobile and two volunteer brigades were orderd to move as quickly as possible from Warrington to positions north of Widnes. The northern flank of the British defensive line was to be guarded by the volunteer cavalry brigade.

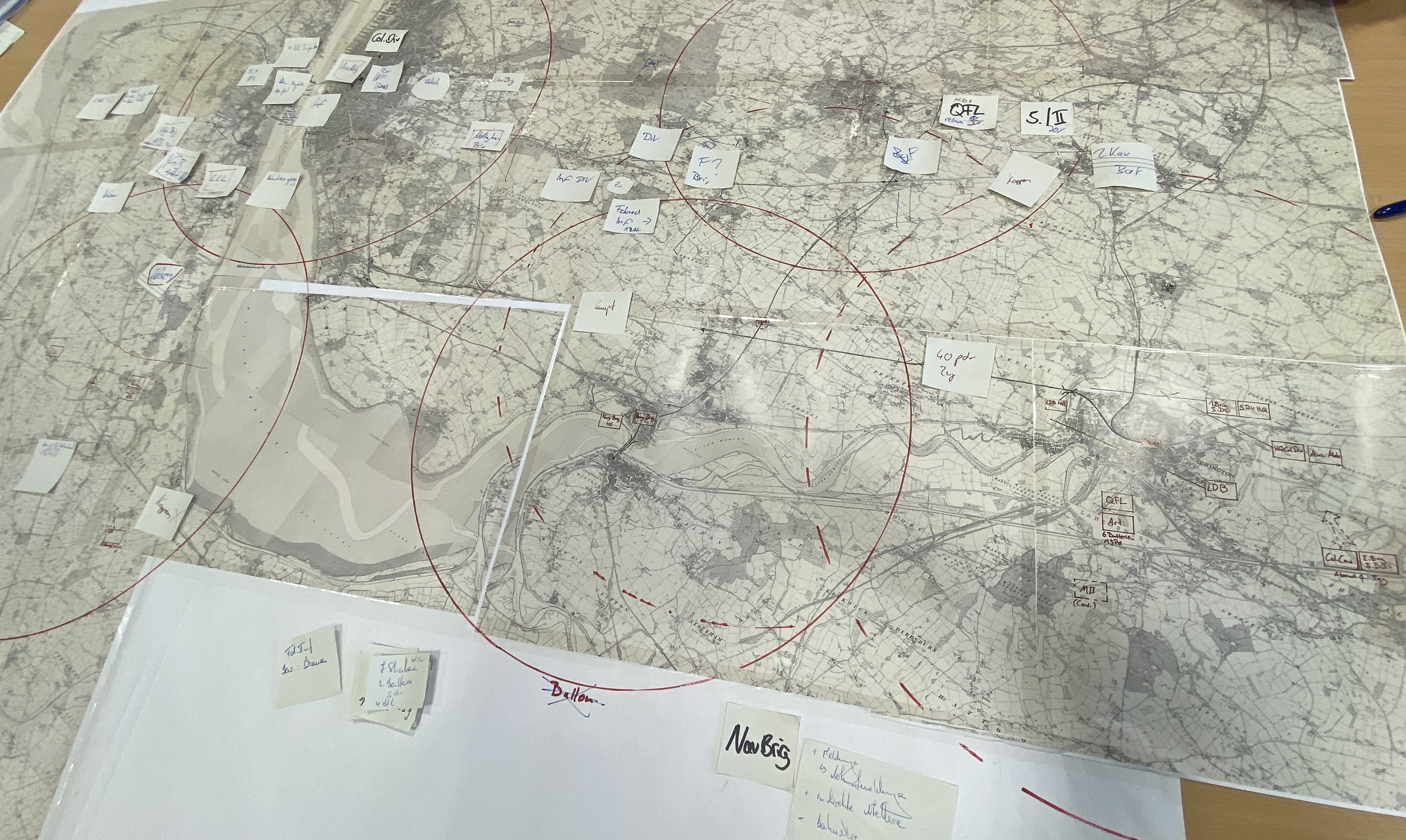

fig. 5: British positions around Warrington.

fig. 5: British positions around Warrington.

fig. 6: British naval brigade holding Widnes.

fig. 6: British naval brigade holding Widnes.

On the Wirral peninsula, the third volunteer brigade was to hold the southern parts of the peninsula together with the Highland brigade. For the second day the general idea was to try to develop an attack against Liverpool harbour.

fig. 7: British positions on the Wirral peninsula; volunteer brigade in the distance, Highland brigade nearest to camera.

fig. 7: British positions on the Wirral peninsula; volunteer brigade in the distance, Highland brigade nearest to camera.

As noted above, both plans were plausible. The French plan was more specific with regard to the second day, while the British had already factored in that whatever happened on day one would make it necessary to plan anew for the second day. The French had correctly identified the train-mounted infantry as one of their key capabilities and planned to employ them accordingly. Both plans also displayed minor flaws: the British plan was slightly over-optimistic with regard to their brigades’ ability to defend Widnes and the postions to the north of the town, while the French plan made little accommodation for possible threats to their rear. Both would have consequences on day one that were nothing short of dramatic.

IV. Day one - the near destruction of the Liverpool Field Force.

And so it began. During the early hours of the battle British force commanders on the Birkenhead map, realizing that an anticipated attack by French forces would not materialize, decided to take things into their own hands and launched an attack against Birkenhead. On the Liverpool map, French forves started to move towards their objectives, and did so quickly and effectively. While the cavalry division was eventually stopped in its path by the British volunteer cavalry brigade, the infantry division launched a well-executed attack against Widnes; after a few hours of heavy fighting, British lines collapsed. The naval brigade was completely annihilated, while 1/5 Division and the volunteer brigades employed north of Widnes took heavy losses. Further northwards, the Australian mobile brigade fared better, finding a spot north of St Helens where it managed to push towards Liverpool without drawing too much enemy attention. The loss of Widnes was already bad news for the British, but worse was to come: while French forces were battling British cavalry, the French brigade of railway infantry managed to push deep into the enemy rear, and by a combination of a little bit of luck and much determination successfully truned southwards towards Warrington. Once they realized the danger, British forces frantically tried to prevent the French units from reaching Warrington, but to no avail - French infantry took the town, captured the British corps casualty collection point, severed many communication lines to the rear and prepared for all round defence.

fig. 8: Successful raid by the French - Warrington has been captured.

fig. 8: Successful raid by the French - Warrington has been captured.

Both sides realized the importance of Warrington and how precarious French forces’ hold of the city was. While the British tried to turn some of their forces around and push the French out of Warrington, the French looked for a gap in the British lines, found it and threw their bicycle infantry brigade into it, which raced towards Warrington to make contact with French units there - and on their way overran 5 Division’s divisional command point.

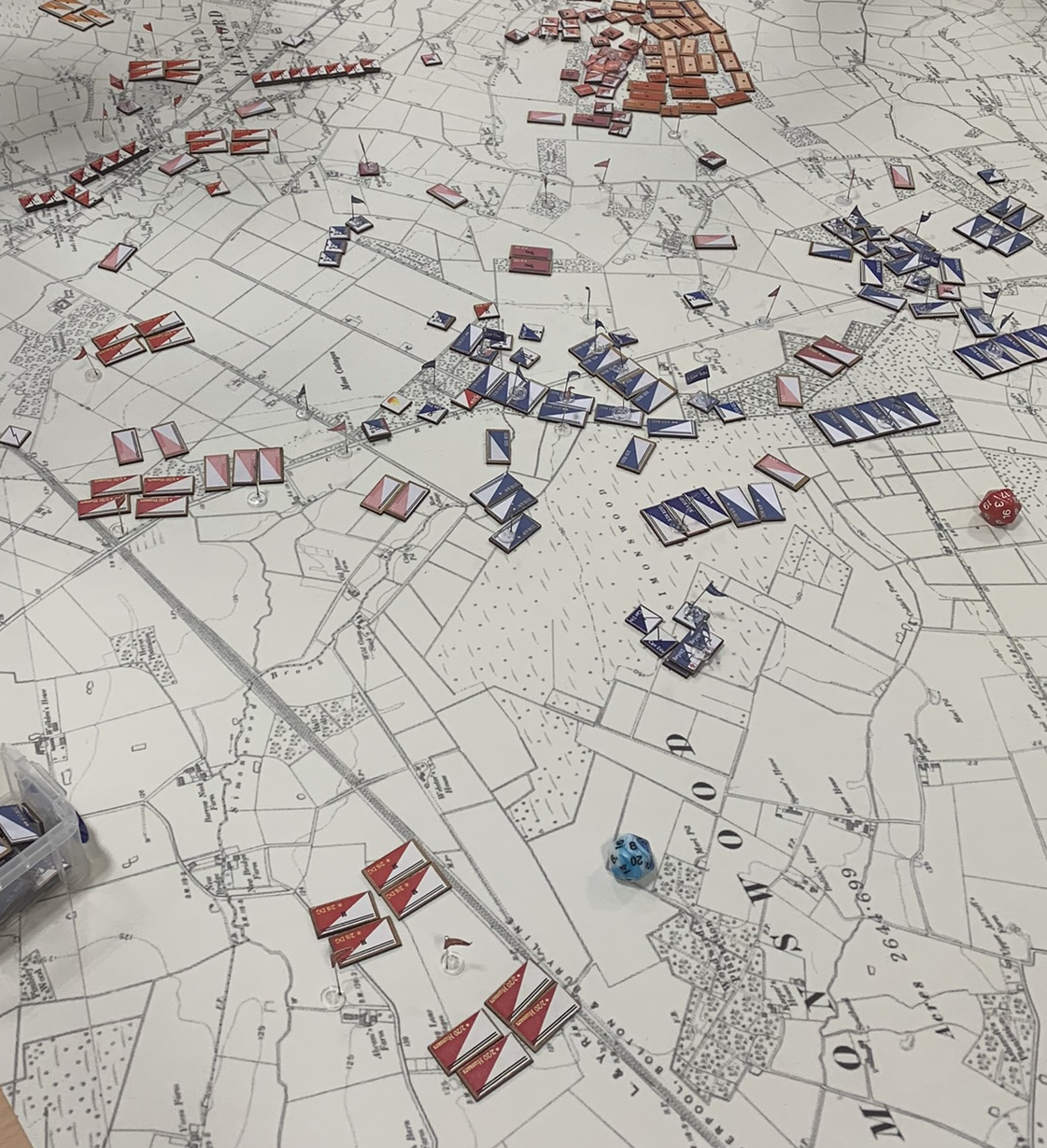

fig. 9: Widnes and Warrington have fallen.

fig. 9: Widnes and Warrington have fallen.

While the British cavalry brigade was fighting a bitter battle of attrition against the French cavalry division, and the Australians somehow managed to get by with very little losses, British positions south of St Helens were effectively oblitterated.

fig. 10: Cavalry battle north of St Helens.

fig. 10: Cavalry battle north of St Helens.

At the end of day one, French forces had both Widnes and Warrington under control, with British forces retreating disorderly to the North-East.

fig. 11: The situation on the Liverpool map at the end of the day, Widnes in the upper right.

fig. 11: The situation on the Liverpool map at the end of the day, Widnes in the upper right.

On the Birkenhead map the situation was somewhat reversed. The Highland brigade had launched a full-blown attack, tyring to blunt-force its way into the city, and was gaining ground.

fig. 12: Highland Brigade attacking into Birkenhead.

fig. 12: Highland Brigade attacking into Birkenhead.

The French infantry division there was suffering significant losses, as British infantry was pushing ever closer to the pontoon bridge that connected Liverpool and Birkenhead. Crucially, however, British commanders had decided to take the French head-on, which, while causing enormous difficulties for the latter, prevented the British from wheeling around Birkenhead and occupying the key ground north of the town which commanded the approaches to Liverpool harbour and would have spelt disaster for French reinforcements.

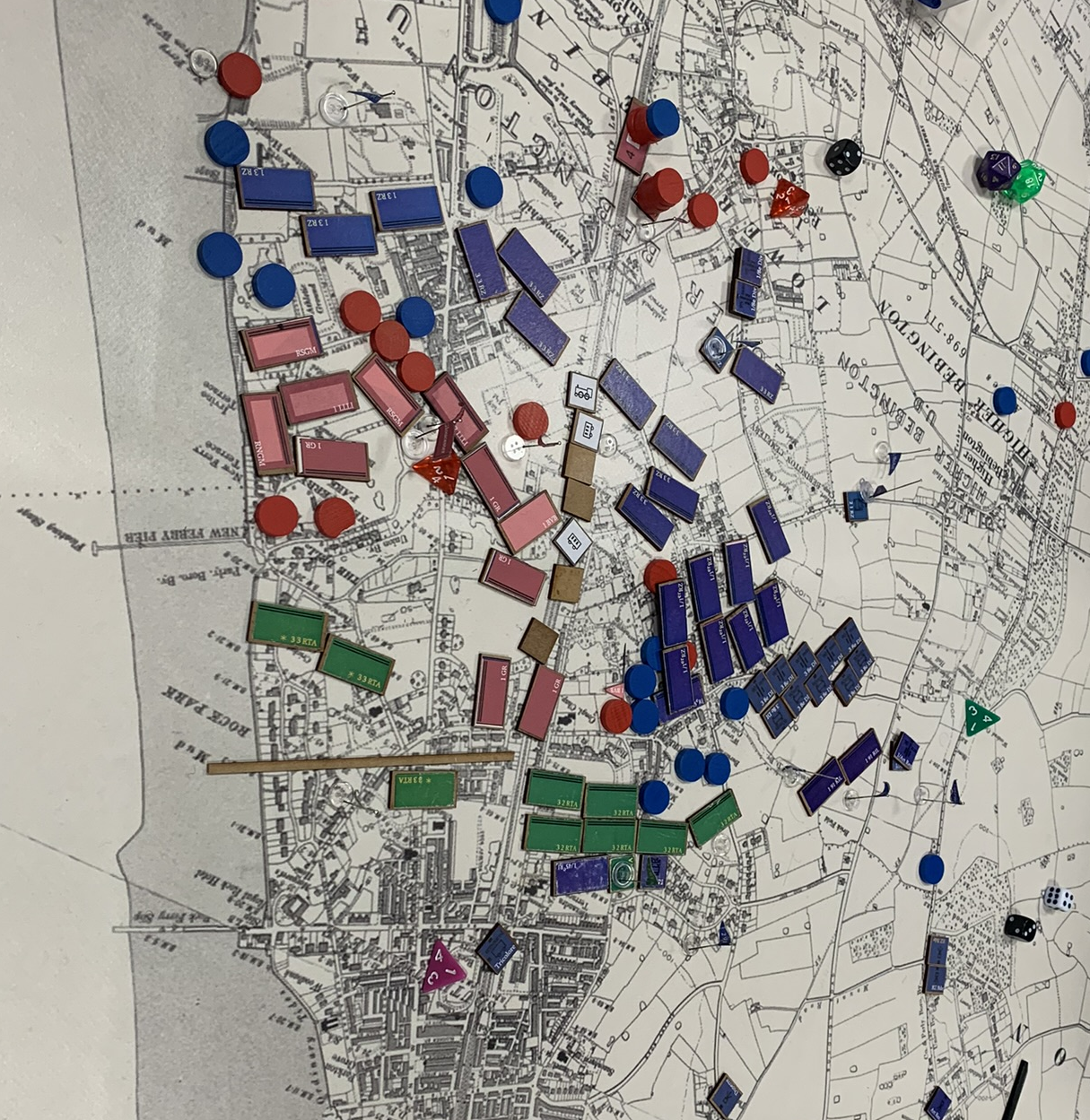

fig. 13: The situation on the Birkenhead map at the end of the day.

fig. 13: The situation on the Birkenhead map at the end of the day.

While these events played out on land, British torpedo boats tried to neutralize the two French gunboats, which were operating very effectively in support of their land forces - but in vain. In a spirited engagement near Hillbre Island, all torpedo boats were sunk by the French gunboats.

fig. 14: French gunboats defeating British torpedo boats.

fig. 14: French gunboats defeating British torpedo boats.

V. Day two - snatching victory (sort of) from the jaws of defeat.

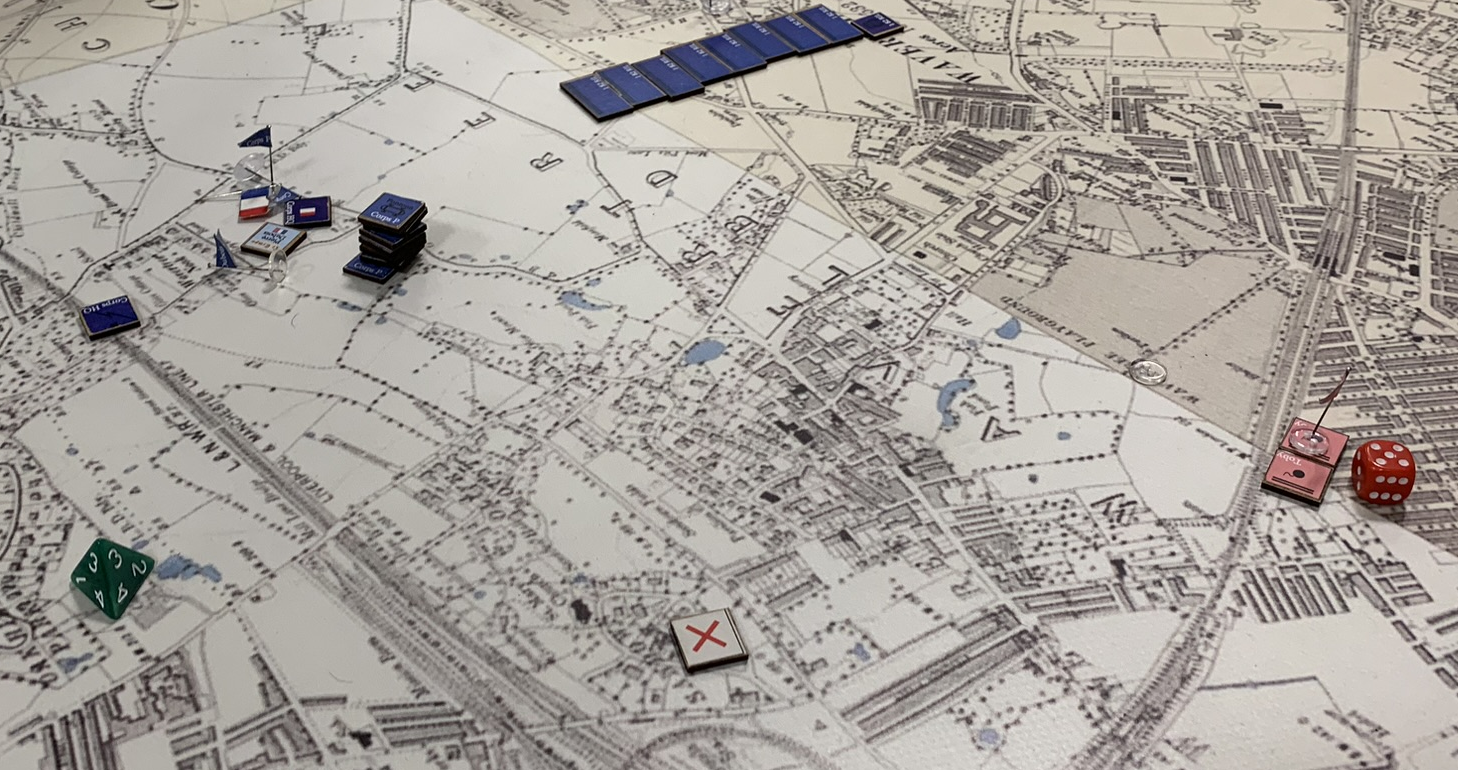

The two teams went into the evening with two rather different assessments of the overall situation. The French team was confident, as their plans had exceeded their expectations on the Liverpool map, while on the Birkenhead map their lines had held, even if they had suffered considerable losses. The British rear on the other hand was in disarray, and given the losses in the Widnes - Warrington area, the British team was staring defeat in the face. In addition, French reinforcements could arrive as the British torpedo boats had all been lost, while British reinforcements were delayed by teams of French saboteurs. The French staff decided to send the cavalry brigade as well as one infantry brigade to the Wirral peninsula, while the second infantry brigade was to reinforce units on the Liverpool map.

fig. 15: French cavalry brigade on Wirral peninsula.

fig. 15: French cavalry brigade on Wirral peninsula.

The British staff assigned one infantry brigade and a couple of artillery batteries to the Wirral peninsula, while the remaining units were all sent to the Liverpool map, arriving at a railhead to the North East of Warrington.

fig. 16: British reinforcements north of Warrington.

fig. 16: British reinforcements north of Warrington.

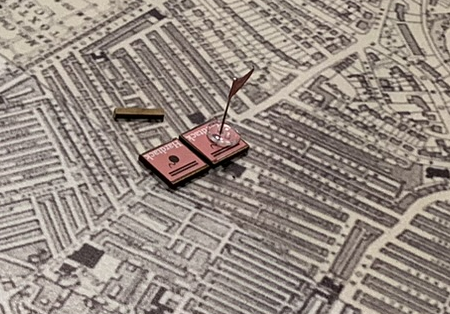

While reinforcements arrived mostly as planned, the umpires - mischiefly minded as they are - had two unpleasant surprises for both staff teams: a famous journalist arrived at French Corps HQ together with orders from the highest levels of command to render him any assistance he required.

fig. 17: Famous journalist Pierre Dubois makes his appearance at the Corps HQ.

fig. 17: Famous journalist Pierre Dubois makes his appearance at the Corps HQ.

And he required a lot: well known for his gripping reports from the front lines of conflicts from all over the world, he wanted to see the immediate frontline at three different places, which meant the staff had to detail someone moving him around - and making sure that nothing untoward happened to him; as it turned out, that was more easily said than done. Understanably the French staff was not happy about a VIP popping up in the middle of their successful operation, but they were not alone in their plight.

The British staff had been provided with the decidedly disturbing news that one of the favourite grand nieces of HM The Queen had been last seen among throngs of civilians fleeing Liverpool. These were represented on the map with individual tokens, and the British now had to check them individually whether the VIP they were looking for was among them (ie whether the name of the VIP was on the underside of the respective civilian token). This tied down cavalry which was soon running around in the British rear and looking for civilians. Luckily, they found them fairly soon and organized railway transport to get her to the rear. To the credit of the British staff, they allocated significant resources to this search, calling back one of their few operable armoured trains to provide tranasportation for their VIP.

During the first few hours operations continued on both maps; on the Liverpool map French forces prudently secured Warrington and remained largely inactive in the South to consolidate their positions. Trouble, however, was brewing up in the North where British cavalry, now in divisional strength, was making earnest attempts at getting into the French rear and breaking into Liverpool.

fig. 18: Heavy fighting, with French cavalry now outnumbered.

fig. 18: Heavy fighting, with French cavalry now outnumbered.

fig. 19: British cavalry units achieving the decisive breakthrough.

fig. 19: British cavalry units achieving the decisive breakthrough.

Even more dangerous, the French staff had left Liverpool largely unoccupied, which included its own HQ, ignoring pre-battle reports about widespread civilian unrest. Around noon, all hell broke loose in the French rear, with several groups of British insurgents starting to attack railway infrastructure, telegraph lines and even managing to briefly overrun 4e Corps’ HQ!

fig. 20: British insurgent teams.

fig. 20: British insurgent teams.

fig. 21: British insurgents near the French corps HQ, which is unguarded.

fig. 21: British insurgents near the French corps HQ, which is unguarded.

The French now had to pay the price for insufficiently covering their rear, and while they doggedly tried to regain control of the city, British cavalry supported by the Australian mounted infantry brigade pushed energetically forward and into the northern parts city.

fig. 22: Australian mobile brigade pushing into Liverpool.

fig. 22: Australian mobile brigade pushing into Liverpool.

Savage house-to-house fighting ensued, and British forced managed to push the French ever closer to the pontoon bridge, occupying - crucially - the nothern coastline from which the harbour could be controlled. Losing this key area did not bode well for French prospects.

fig. 23: British units pushing deeper into the city.

fig. 23: British units pushing deeper into the city.

fig. 24: British units now in control of most of Liverpool.

fig. 24: British units now in control of most of Liverpool.

fig. 25: Chaos in the French rear.

fig. 25: Chaos in the French rear.

Further east, however, things were different, and rather astonishingly so. After several hours of comparative inaction, which had allowed 5 Division to consolidate their positions north of the Warrington - Liverpool railway line, French commanders decided to attack.

fig. 26: French and British lines near Warrington.

fig. 26: French and British lines near Warrington.

fig. 27: French lines connecting Widnea and Liverpool.

fig. 27: French lines connecting Widnea and Liverpool.

Usually, such decisions have mixed outcomes at best, but here, capably supported by French heavy artillery, the result was devastating: most of 5 Division was destroyed, as were the remnants of the two volunteer brigades in the area.

fig. 28: Collapse of British units north and northwest of Warrington.

fig. 28: Collapse of British units north and northwest of Warrington.

While heavy fighting also caused significant losses among the French, when the order to move back to Liverpool finally came, there was still a fairly sizeable force available. This then, however, ran into the British cavalry now dominating the area around St Helens, and in the ensuing chaotic battle French forces were prevented from regaining Liverpool, suffering more losses instead at the hand of British cavalrymen.

fig. 29: French units facing British cavalry preventing them from reaching Liverpool.

fig. 29: French units facing British cavalry preventing them from reaching Liverpool.

During the confused fighting in the city, the French journalist was first captured by British insurgents and then killed when French forces tried to free him.

While in the early afternoon the glimmer of hope that had emerged around noon for the British side had grown into a fairly substantial light, the situation on the Birkenhead map was very different.

fig. 30: Renewed attack on Birkenhead.

fig. 30: Renewed attack on Birkenhead.

Here, a mixture of bad luck and questionable operational decisions had let commanders commit their reinforcements to their frontal assault of the city, which eventually failed and resulted in the destruction of all British units as effective fighting forces.

fig. 31: Remnants of British units in Birkenhead, now encircled.

fig. 31: Remnants of British units in Birkenhead, now encircled.

A sudden push forward by French cavalry nearly caused the British HQ to be overrun, but luck held with the British. Yet on the whole British attempts on the Birkenhead map had utterly failed, and at great cost. However, by tying down a sizeable part of French reinforcements, all had not be in vain; it is likely that had the French committed more of their infantry to Liverpool earlier - they started doing so late in the afternoon -, the city might have held.

fig. 32: Birkenhead free from British units.

fig. 32: Birkenhead free from British units.

As it turned out, at the end of the day the French controlled Birkenhead, some parts of Liverpool and a stretch of Land towards and including Widnes. They did not, however, control the harbour, and British batteries were in position covering all approaches by sea from the northern part of the city; 4e Corps, which had suffered significant attrition, with many units down to less than 50%, had lost its vital supply point. The British team had managed to pull it off, but barely. British losses had been considerable, with 5 Division as well as nearly all independendent brigades destroyed and only British cavalry together with the Australian mobile brigade still capable of any action.

fig. 33: Little remains of 5 Division but the remnants of 2/5 brigade.

fig. 33: Little remains of 5 Division but the remnants of 2/5 brigade.

The blue team, on the other side, was likewise pretty battered, and while there was still some fight in the naval division, the other two infantry divisions had bled considerably and most of the heavy artillery was gone. Even without the loss of their logistical lifeline the French were hardly in a position to resume fighting the next day. A British victory, then, but barely.

VI. A few final thoughts.

First of all, both teams, staff as well as force commanders, deserve a lot of praise for the determination with which they continued to fight even against difficult odds and in the face of looming defeat. Simulations like PdB only work if participants commit themselves to the exercise, and committing themselves they did! The staff teams processed hundreds of reports by their force commanders, tried to keep up with events - sometimes with more, sometimes with less success - and quickly accommodated for unforeseen turns like the introduction of VIPs to the scenario. On the maps, force commanders did not shy away from kneeling on the maps for hours on end, living in two-minute turns mercilessly enforced by the umpires.That they did not shirk from what was physically quite exausting even as frustration mounted is worthy of praise as well.

Then, the plans. As is nearly always the case, the plans were sound, and in this case - that is a bit more unusual - the French plan worked out pretty well, at least on day 1.

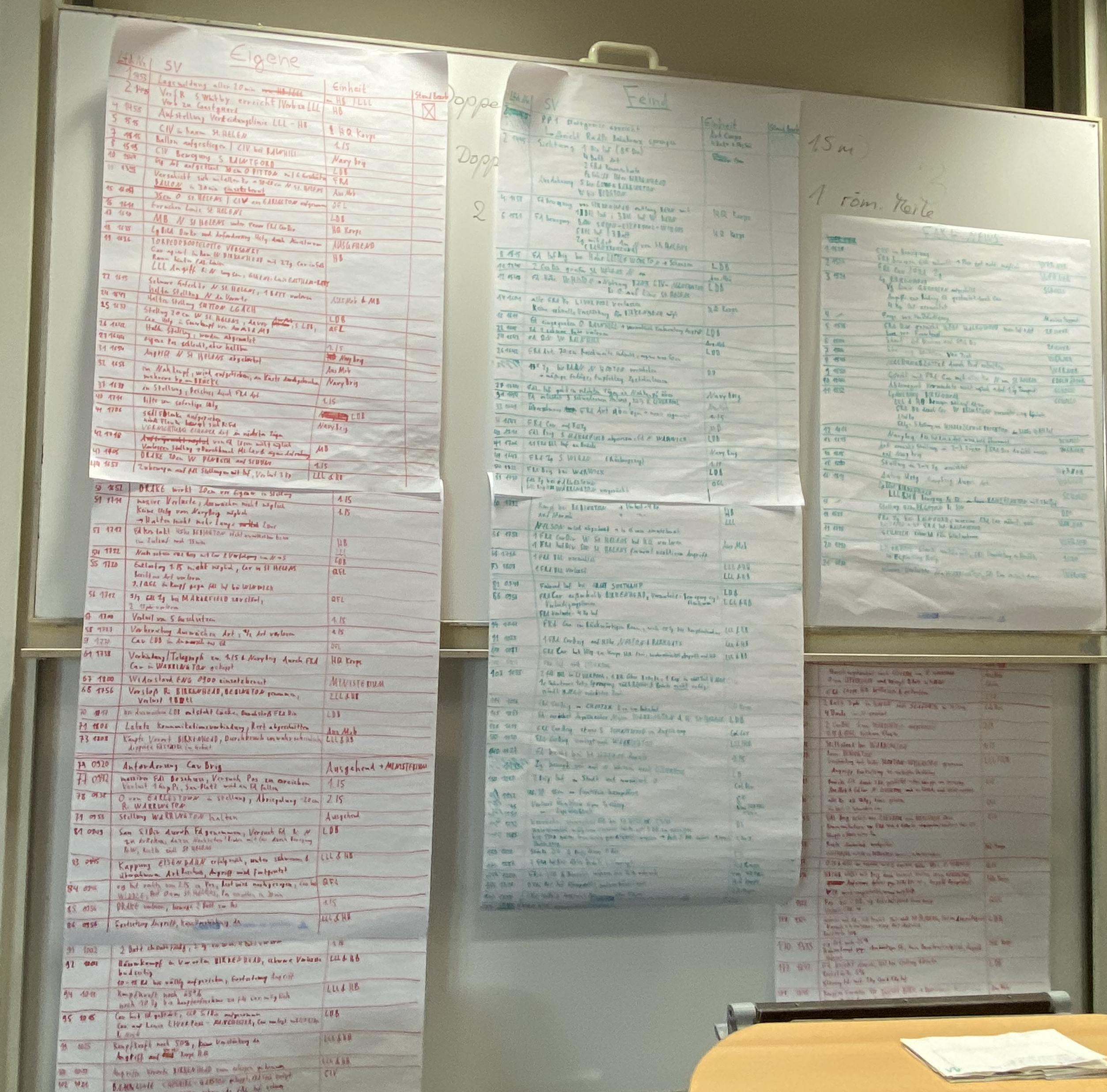

fig. 34: The French staff map.

fig. 34: The French staff map.

Both teams put considerable effort into their plans, and on day one there was at least some reward for it.

fig. 35: British communications logs.

fig. 35: British communications logs.

fig. 36: British staff map.

fig. 36: British staff map.

Both sides also had to wrestle repeatedly with the issue of force commanders having a different view of the situation on the ground and deciding against following orders by their staff teams to the letter.

The elements introduced to the scenario worked well, or rather, as intended. They created further distraction for both the staff teams and the force commanders, and not a little bit of chaos. This was the first time the Conflict Simulation Group experimented with these elements in PdB, and it will definitely not have been the last. The same is true for managing elements of the civilian population, which proved to be burdensome for the force commanders, and introducing off-map action with an effect of the number of reinforcements and the time they were due to arrive. Again this put additional burden on the staff teams, which is why it will become a regular feature in future scenarios.

And finally, regarding the challenges facing participants, PdB once again showed that for all its limitations, it once again excelled at putting its participants under - at times severe - stress, which impacted considerably on their decision making.