Terror on the Tweed! A smaller game of Pluie de Balles.

by Jorit Wintjes

I. Introduction.

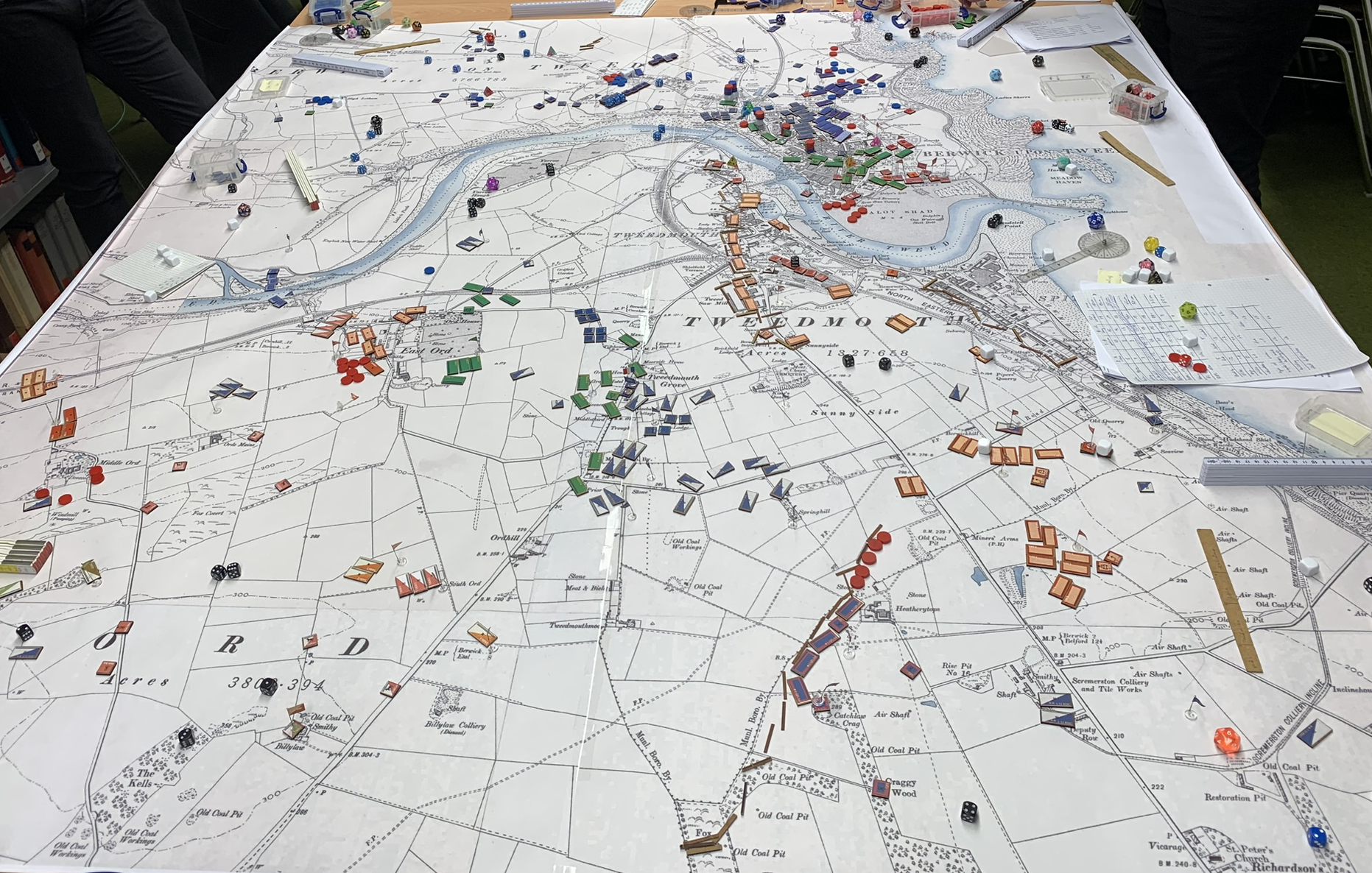

January 9 and January 16 saw another game of Pluie de Balles, this time on a smaller scale with only around 10 participants. As usual they formed two teams - British and French -, of about equal size. Due to the fairly small group only one map was used. The scenario stipulated a French division, heavily reinforced with cavalry and artillery, trying to capture the port city of Berwick upon Tweed. The overall assumption was that after initial landings in the South, French progress towards London had stalled in the face of determined resistance, leading French high command to entertain plans for diversionary attacks along the British coastline. One of these attacks saw a French force descending on the coast West of Dunbar and then, instead of pushing towards Edinburgh as British High Command expected, turn southwards and move towards Berwick upon Tweed, where a Royal Navy station operated a number of Torpedo Boats which had done a considerable amount of harm to French logistics. The overall French plan was to capture the port and the press on further southwards towards Newcastle. British reaction came late; apart from a Navy Brigade defending Berwick a number of colonial units were hurriedly set in march towards Berwick, the first battalions arriving just in time before the French attack. It was in the face of this French onslaught that British units had to hold on to Berwick for dear life, hoping that eventually further reinforcements from the south might break the French attack. Going by this scenario, the French mission was fairly straightforward: they had to capture Berwick by forcing their way into the city and at the same time fend off any British attempts to reinforce the city and fall into the flanks of the French attack. Conversely, the British mission was to hold the city as long as possible, thereby buying reinforcements time to develop a flanking attack against French forces.

II. Force Structure.

The French force moving towards Berwick consisted of an infantry division - 9e Division d’Infanterie - composed of two brigades of experienced infantry, Zouaves and Algerian Tirailleurs. The division was further reinforced by an elite brigade of heavy cavalry and, crucially, two batteries of 120mm guns, a battery of 220mm siege mortars and a battery of 240mm siege guns; if operated properly, this concentration of heavy guns could wreak havoc to British defensive positions in and around the city. In all, French forces amounted to 12 battalions, 8 squadrons of cavalry, 8 field guns and 16 heavy and superheavy guns. The French also had a gunboat operating off the mouth of the Tweed.

An overview over French and British force structures.

The British force was initially built around a powerful naval brigade of two battalions of infantry, four field guns, four heavy guns and three superheavy guns. In addition, three battalions of Australian infantry were available for reinforcing the defences of the city; to the south of Berwick operated a small mixed brigade of two weak battalions (about 50% in strength), two batteries of four guns each and two squadrons of heavy cavalry; additionally, a 12in railway gun was available. The overall total on the British side thus amounted to about six battalions infantry, two squadrons of cavalry, 12 field guns and 8 heavy and superheavy guns. Initially, an Australian mobile brigade of four battalions mounted infantry and two batteries horse artillery was supposed to arrive as reinforcements, but eventually a cavalry brigade of seven squadrons of cavalry and two batteries horse artillery as well as three further battalions infantry made it to the battlefield as well; overall, British reinforcements amounted to seven battalions, seven squadrons of cavalry and 16 field guns. In addition, the British team had operational control over three torpedo boats stationed in Berwick.

III. Initial Dispositions.

The British navy brigade was positioned in and around the walled town centre of Berwick, while the Australian battalions had taken up positions in Tweedmouth. To the South, the Queen’s French Legion occupied positions west of the coastal railway; while the infantry was dug in, there was a distinct gap between their positions and friendly units in Tweedmouth. Cavalry and horse artillery was supposed to cover this gap.

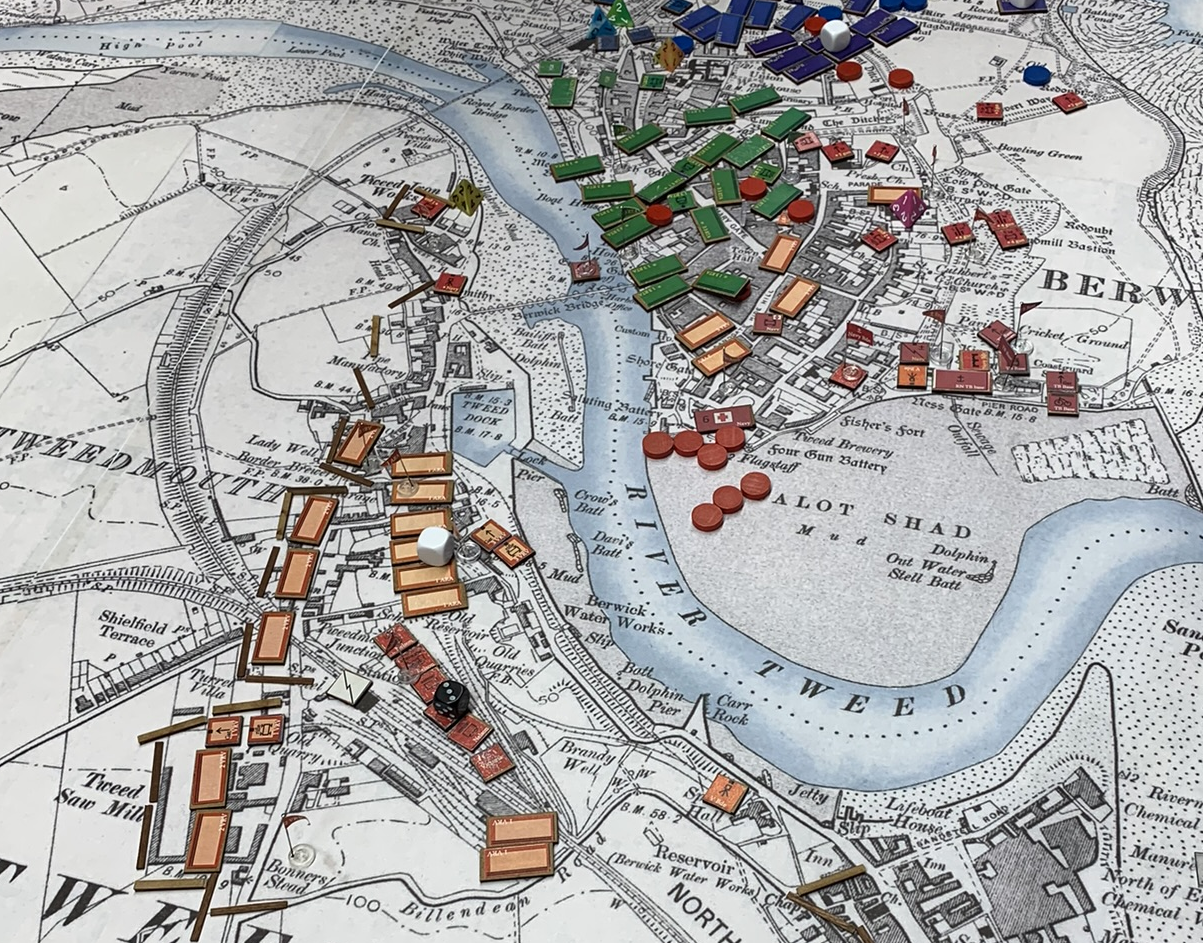

British and French dispositions.

British dispositons.

The French had thrown a pontoon bridge across the Tweed and positioned their divisional HQ in East Ord. To the south of the village stood the French heavy cavalry brigade, ready to cover the flanks of the French attack, which was to develop on the northern bank of the Tweed. There, the two infantry brigades were positioned side by side, with the heavy artillery starting to prepare positions on the heights to the north west of Berwick.

French dispositions.

IV. The French attack.

North of the Tweed, the French attack took time to develop; for quite some time the battle took on the character of an artillery duel, before eventually the French brigades started to move towards the city. While French progress initially was slow, clever, consistent and determined use of their artillery soon caused significant losses among the British defenders.

The effects of French heavy artillery firing into the city.

South of the Tweed, the situation could not be more different. While British positions appeared to be quite formidable, the French cavalry commander threw his brigade aggressively into the gap between the Queen’s French Legion and the Australians holding Tweedmouth, taking out most of the British cavalry and the horse artillery, and then turning to attack remainder of the British brigade from the rear. Within half an hour, the Queen’s French Legion had ceased to exist as a combat capable unit, with only five companies of infantry and four squadrons of cavalry surviving. This not only enabled the French to cut the railway line southwards, thus making it impossible to bring reinforcements directly into the city, but also removed any imminent threat to the French attack from the South.

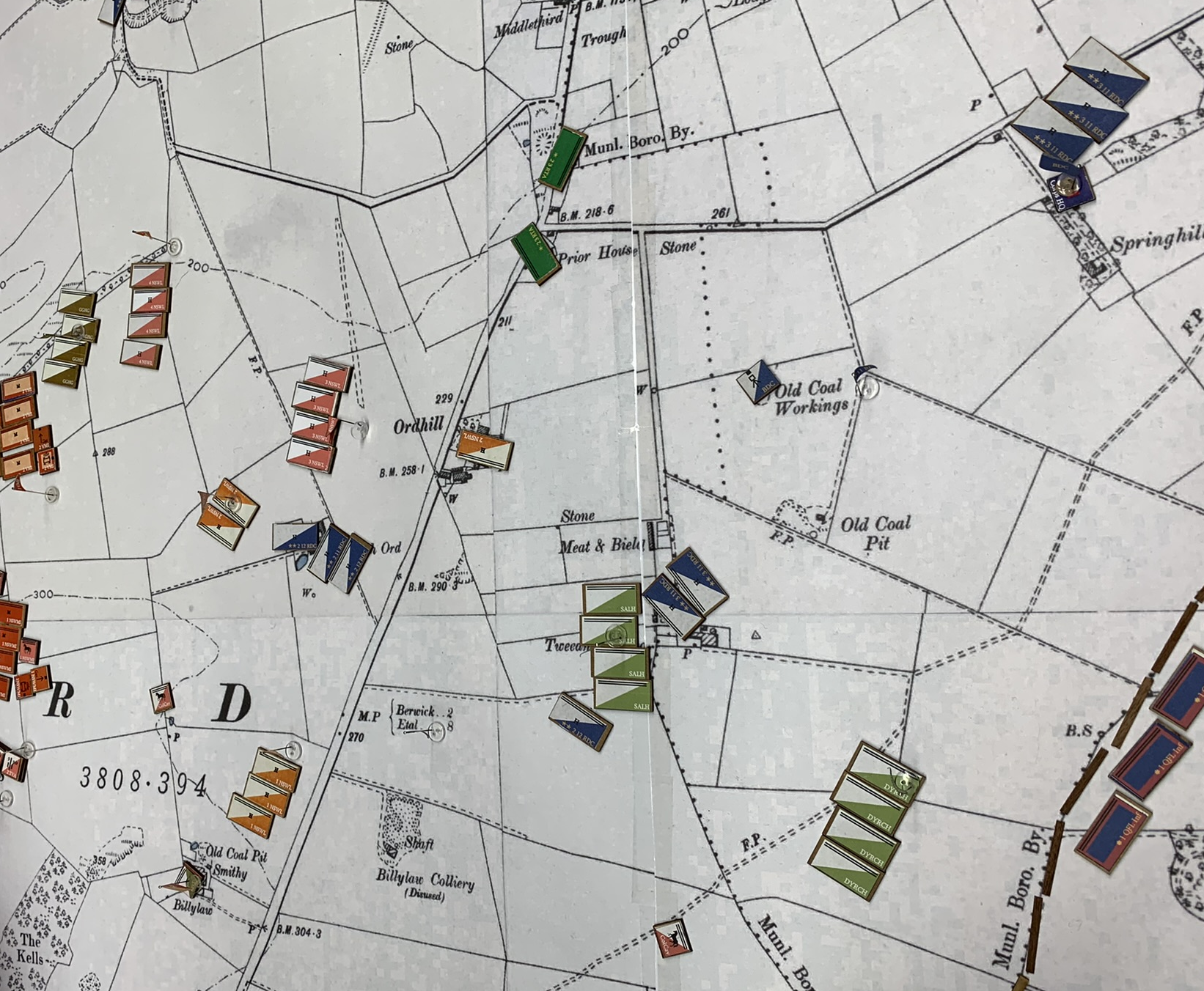

French cavalry surging forward.

French cavalry starting to exploit their breakthrough.

At that point, fighting ended on the first day. A lull in the fighting was assumed allowing units to reorganize themselves and British reinforcements to appear. When participants reconvened a week later, both sides felt increasing pressure - the French, as British reinforcements could eventually frustrate their attempts at capturing Berwick, the British, as the French attack was gaining momentum and seemed unstoppable safe a dramatic turn of events south of the river.

The situation at the end of the first day; note that most British units in the lower right quadrant of the map have been destroyed by French cavalry.

V. British attempts at turning the tide.

As the railway line to Berwick had been cut, British reinforcements arrived on the southern edge of the map to the West of the railway line. The two brigades, one of mobile infantry and one of cavalry, were certainly impressive to look at!

British reinforcements.

The British plan was to use the cavalry brigade to engage French cavalry, thereby allowing the mobile infantry to push into East Ord, dislodge the French divisional HQ and bring the brigade’s artillery to bear on French infantry on the northern banks of the river. The plan was sound in principle, and as the British cavalry brigade included two batteries of horse artillery - something not available to the French cavalry commander -, it had good chances of producing results. Or so it seemed.

In reality, as soon as the British cavalry brigade moved forward, it was attacked remorselessly by French cavalry trying to hack its way through to the mobile infantry; within half an hour the whole area west of the railway line was one huge arena where cavalry squadrons were fighting small individual battles. The cavalry battle raged for quite some time, and a few French squadrons managed to break through the British brigade, first taking out most of the British artillery and then reducing the mobile infantry brigade to a collection of disorganized and leaderless infantry companies. While the latter eventually made it into East Ord, the French had by that time evacuated their divisional HQ eastwards and were pounding the village with their field artillery.

The chaotic cavalry battle.

With the French cavalry brigade tying down British reinforcements, French forces north of the river were free to push their way into the city; savage house-to-house fighting ensued, and while the French suffered considerable losses, the combination of firepower provided by the heavy and superheavy artillery batteries and their considerable numerical superiority made the outcome inevitable: with the last defenders isolated near the harbour, the French eventually captured the city.

Initial French assault into the city.

French forces pushing deep into Berwick.

At that point, it was time to call it a day. The British team had fought with great determination, but French victory was complete.

General situation at the end - note British reinforcements practically destroyed as combat-capable units.

VI. Some final thoughts.

While the resilience of British defenders in Berwick exceeded even the expectations of their own commanders - who estimated they would last about half an hour on the second day; it turned out to be about four… -, in the end they were soundly beaten. This was largely due to two factors: the expert use of the heavy batteries assigned to the division, which were constantly raining shells onto British positions and managing astonishing rates of fire (in Pluie de Balles, the mechanism covering indirect fire is intentionally complicated to limit the rate of fire; the battle for Berwick showed that determined and resourceful participants can overcome these limitations), and the sterling effort by the French cavalry brigade, which took on three enemy brigades in succession, rendering all of them incapable of further action and losing less than 25% of its own strength in the process. The topography to the south west of the city certainly was conducive to cavalry operations, but the French success there was nevertheless nothing short of stunning. Even so, it took the French a very long time to capture the city, as British defenders made clever use of their limited capabilities and made the French pay for every street in Berwick.

From an umpire’s perspective, perhaps the most fascinating thing to observe was the level of immersion the whole exercise created. Both teams were determined to give their best right to the end, something all the more commendable as due to administrative constraints the battle had to take place on two consecutive Tuesdays; while one would expect this to break immersion and have a negative impact on the participants’ commitment, quite the opposite was the case. In the end, the battle for Berwick once again proved that the success of any wargame is directly related to the level of commitment by the participants.