The post-mortem – some musings on the ins and outs of discussing Kriegsspiel results with Kriegsspiel participants

by Jorit Wintjes

In running a wargame of the Prussian Kriegsspiel type there are only a few really important ground rules, and – please excuse the somewhat weak attempt at a pun – the rules for running the Kriegsspiel are not among them. True, they are required for aiding the facilitators in having units move and enter combat, but, having the educational purpose of the Kriegsspiel in mind, they are only a distant second in importance to the three main rules of running a Kriegsspiel.

One, if at all possible, a Kriegsspiel should be run in real time. This is of course a major imposition on the facilitators and requires, depending on the size of the scenario, a large number of assistants in the facilitating team. However, in order to expose the participants at least in some way to the friction and the delays that will invariably occur – even on a 21st c. battlefield communication can and will be interrupted – a real time simulation is usually preferrable to turn-based simulations, unless the latter match turn length (which has to be rigidly enforced) with actual time, something exceedingly rare in turn-based simulations. While Kriegsspiel rules do indeed mention two-minute turns, these serve only as an aid to the facilitators, providing them with a measurement allowing to determine movement or weapons effect to the minute.

Two, again, if at all possible, participants in a Kriegsspiel should ideally be physically separated from each other. An educational Kriegsspiel is an exercise in command first and foremost, and in order to maximize the learning effect each team should be prevented from socially interacting with their opponents, concentrating instead on the work they have at hand. Again, and particularly in the case of larger scenarios with multiple levels of commands (for example with participants forming both brigade and divisional staff or divisional and corps staff teams), this can make for somewhat complex logistics in that either sufficient rooms need to be found or parts of the participants’ rooms at least walled off temporarily; the facilitators should always have a room for themselves.

By far the most important rule, however, is rule number three – always have a meaningful post-mortem discussion. The discussion after the Kriegsspiel has finished is by far the most important element of the whole exercise, if the Kriegsspiel is run for educational purposes, that is. This was already recognized and pointed out, indeed stressed by Prussian Kriegsspielers, yet, unfortunately, however, post-mortem discussions can actually be a slightly tricky thing, and the main point of these brief note is to highlight some of the issues that can raise their not overly handsome heads when entering a post-mortem discussion.

A key issue facing facilitators entering such a discussion is also an almost blatantly obvious one: very often, one side becomes an excellent second, while the other ends the game as penultimate – which is an admittedly not terribly witty way of stating a simple yet almost brutal reality: one side wins, while the other loses. This in itself can create a situation that is somewhat socially awkward; in a military context, with military hierarchy entering the equation, there is a certain danger that this awkwardness is actually intensified. In fact, one could argue that, while post mortem discussions should be done with great openness and with a spirit of “what is said in the room stays in the room”, they are in fact social exercises in themselves, demanding skills from the facilitators as well as the participants that, while different from those in demand when actually running the Kriegsspiel, are no less important; perhaps the most important one is the ability to learn from mistakes. While some of the social awkwardness can be removed by having outside expertise on hand for running the Kriegsspiel, the ability to evaluate one’s own action is crucial to the learning experience of any Kriegsspiel. When reviewing the action, participants need to look beyond the actual results and ask themselves how their decision-making process developed throughout the exercise, whether they processed all available information correctly and whether their communication was sufficient to inform their subordinates (represented by the facilitators) of their intentions.

Looking beyond the actual result is not always easy; the authors have repeatedly made the experience that at some point, some participants start to complain about certain decisions made by the facilitators, or blame luck, dice or a combination thereof for the outcome. While understandable, particularly for the side that lost, it is by entering such discussions that participants start to evaluate the simulation itself, rather than their own decision-making processes and actions. For the facilitators it is important, then, to explain (again, this should also be done before the start of the exercise) that the Kriegsspiel is not about interacting with the game mechanics; it is about testing one’s own decision-making process against that of an opponent actively trying to outthink oneself. To some extent, the outcome of individual engagements throughout the battle is therefore only of secondary importance. This also means that during a post-mortem discussion, the winning side cannot lay back in the comforting knowledge of having done everything as it should be, for that may not have been the case at all. Again, the authors have made the experience that overall success can result in shortcomings in the decision-making process being explained away with the sentence “but in the end it worked out well”, and just as with complaints about individual decisions it is necessary that facilitators explain why it is very well possible that there is more to say about decision making issues with the winning side than with the losing side.

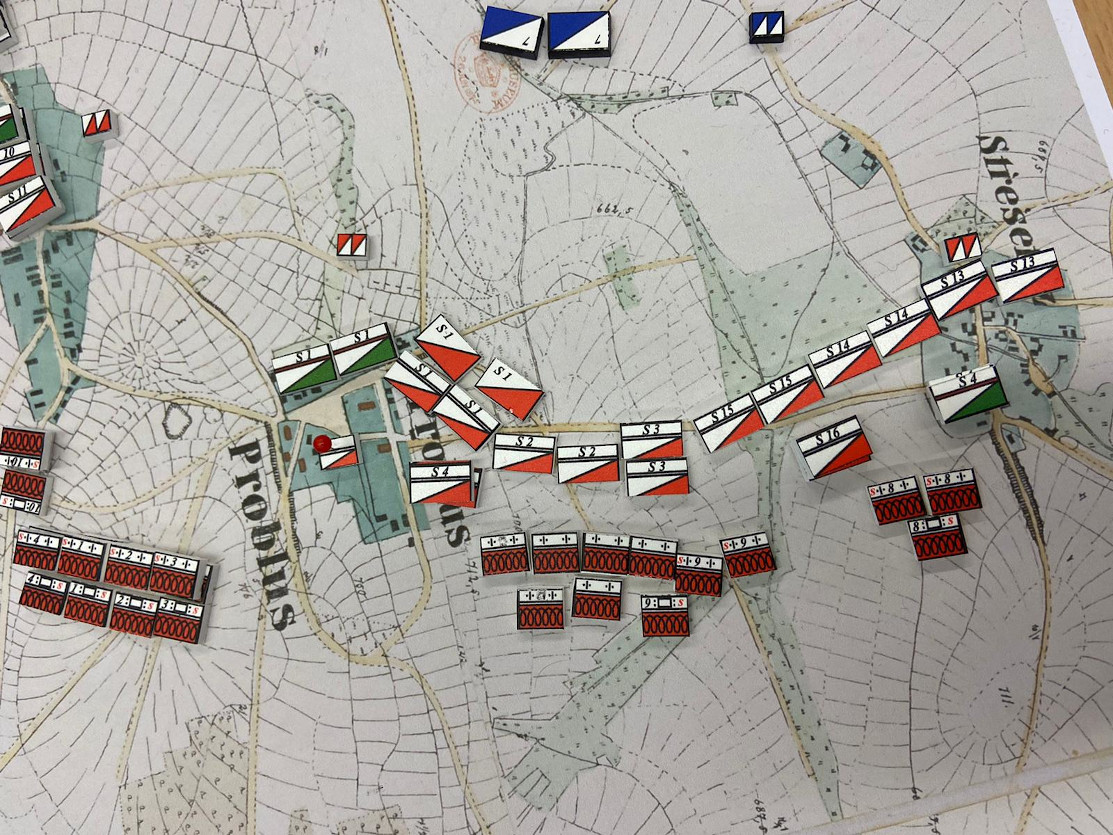

A Kriegsspiel type wargame that the authors recently run at a NATO member state service academy provides a good example for the need of explaining to the winning side that their victory was due to what happened on the battlefield much more than to the brilliance of their decision making. In a scenario that ran over three days, the last day saw extremely heavy fighting over some heights, the control of which eventually decided the outcome of the whole exercise. The winning side, having seized these heights on the second day, managed to keep possession of them and by the end of the third day, with heavy artillery firmly entrenched, had basically won. In the post-mortem discussion, however, it actually emerged that the divisional command team on the winning side responsible for initially occupying the heights was not entirely clear about their role, while their corps command (the scenario called for participants forming both army corps and divisional staff teams) was blissfully unaware of their crucial importance at all. On the other hand, the side eventually losing the fight, while doing so partly due to a failure to concentrate properly, was fully aware of the importance of the heights in question from the end of the second day on and consequentially built their operational plans for the third day entirely around regaining them; in fact, as far as planning and the interpretation of the battlespace was concerned, the losing side actually showed a performance that was significantly superior to that of the winning side. In the discussion afterwards it was therefore important to both dampen the enthusiasm of the winning side and lighten up the mood of the losing side.

To go from the example to the post-mortem discussion in general, what, then, makes a successful one? Based on their experience of running Kriegsspiel type wargames with both early and mid-career military decision makers, the authors have found the following points to be of particular importance.

First of all, when discussing events, it is crucial to separate the planning process and the actual plans from what then happened on the simulated battlefield. The plans the participants come up with deserve both scrutiny and being assessed without regard to whether they actually worked or not. Second are communications: how did the participants communicate their intentions to the facilitators (ie, how understandable were the orders given to their subordinate commanders represented by the facilitators) and how did they process the reports given back to them by the facilitators. While a discussion of the respective plans is essentially an evaluation by a party that, while having access to all information, is uninvolved, once communications come into the focus of the post-mortem, so does the actual performance of the facilitators. As, during the course of a possibly intense battle, mistakes will be made by the facilitators it is crucial to be both open about any such mistakes and to explain that in “real life”, subordinates will make mistakes as well. Indeed, it is one significant shortcoming of the Prussian Kriegsspiel that facilitators invariably try to perform as flawlessly as possible, thereby representing essentially ideal subordinate commanders, something unlikely to happen in the real world. There are ways around this problem, but that is the topic for another commentary. And finally, after plans and communications, the actual decision-making process has to come under scrutiny. It is important here to first let participants give their impressions and then lead on with specific questions about how they came to their decisions, when, if at all, they thought it necessary to change their decisions and their overall concept of the battle, what made them change it etc. Discussing the decision-making processes of the two teams is probably the most important element of the post-mortem discussion at all.

Of course, not all discussions are the same, and, depending on the participants, sometimes one might make little headway in asking questions. Even so, just as the Kriegsspiel is itself an exercise worth the effort put into it, so is the discussion afterwards. Therefore, in the unlikely case someone would ask the authors how to run a Kriegsspiel, the first bit of advice would be to generously allow time for the discussion afterwards.

So much for our musings, ramblings really, on the thorny issue of the post-mortem discussion, without which, as the Prussian Kriegsspielers already pointed out, a Kriegsspiel would be fairly useless. Today, nearly 200 years after the introduction of the Prussian Kriegsspiel to the Prussian army, strict military hierarchy is not the problem it was in the Prussian army, but participants still do not like to lose, so the need for distancing oneself from the actual outcome and for evaluating one’s decision-making process is as much of an issue now as it was back then.